Religions developed out of universal concerns. While I can’t hope to compete with the masterful insight of Pascal Boyer, I do have a gut feeling that as soon as humans evolved the ability of foresight we began to worry. Where is that next meal coming from? Will we survive another day? Is there any way to hedge our bets? In ancient times mortality’s unblinking stare would have been much closer to our faces. Even as recently as the Middle Ages death was much more on the mind, much more frequently seen.

One way to ensure survival is to propitiate those gods who control the productivity of the soil. Long before Demeter lost Persephone ancient people mourned the death of gods who ensured fertile soil, hoping against hope that they might come back each spring. I recall the seriousness with which Rogation Days were taken in the Midwest. At Nashotah House the earth itself was blessed. I recall a priest from Central Illinois who gleefully recounted that the University of Illinois crop experiments were always a little skewed because each year he blessed them on Rogation Days, giving Ceres a boost. CPR for mother earth; give us our daily bread.

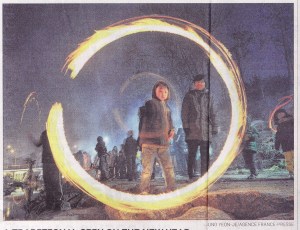

The picture of a South Korean boy spinning a can filled with glowing embers over a field on the first full moon of the Korean New Year reaffirms that concerns are the same everywhere. In our sterilized, indoor, urbanized lives where food is grown, harvested, processed and packaged by others for simple consumption of the vast majority, we have lost one of the most poignant aspects of religion. People pray for survival against the devious plans of terrorists, or the insidious diseases that threaten those who make a living simply moving electrons from place to place. Meanwhile somewhere in a country teetering on the brink of nuclear winter, a young boy swings a bucket full of hope.