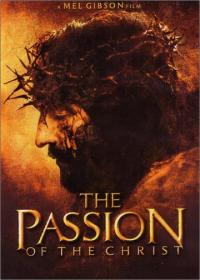

In Holy Horror I make the suggestion that Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ can be considered a horror film. It certainly has more gratuitous blood and gore than many examples of the genre I’ve seen. Really, I had no desire to see it. One of the great aspects of teaching is learning from students. While an adjunct at Rutgers one of my undergrads brought me a copy of the DVD to watch. She said I needed to see it. Obligingly I did so. I knew if I returned the disc to her without watching she’d ask why I hadn’t. Apart from the famously sadistic flogging scene, it was, like any other Bible film, off base quite a bit of the time. This was commentary, not Scripture.

This came back to me reading Bob Cranmer’s account of his haunted house on Brownsville Road in the book about which I blogged a few days ago. Cranmer didn’t exactly follow orthodox methods for driving the demon out of his house. Some of his tactics were improvised. The one I found the most startling was that in the rooms that were most badly affected he played The Passion of the Christ on a continuous loop for weeks at a time. Not only does this suggest demons are capable of watching movies, but that this film can stand in for the actual events that took place in Israel two millennia ago. If the priests involved objected to this method, he didn’t record it. So we have what could be considered a horror movie being used to try to drive out a real life monster (depending on one’s point of view).

Interestingly, this is one of the points behind Holy Horror. Film (and other media) can be a powerful force in our experience of the world. We don’t just go to the cinema because everybody’s talking about a movie. Our experience of watching it is transformative, if only temporary. The same is true of live theater or a concert. Far from being mere entertainment, these cultural events provide a form of transcendence, if they speak to us. In my own case The Passion of the Christ didn’t sell me on Mr. Gibson’s vision. I have no doubts that Roman crucifixion was a horrible spectacle. I also have no doubts that the Good Book indicates that the point of all of this was elsewhere. The Gospels weren’t an effort to traumatize readers. That’s the job of horror movies. Apparently this is something on which even demons agree.