I have to confess that the easy self-publishing of ebooks is a real temptation sometimes. Perhaps it’s one of those inexplicable side-effects of earning a Ph.D., but sometimes you have the impression you have something to say and traditional publishers just don’t agree. In my work life I see many clever ideas that, well, let’s be frank, just won’t sell. Publishers do have to keep an eye on whether a book can earn back the money put into it, and sometimes a good idea leads to no cash payout. So when you can easily sign up online—you don’t even have to talk to anyone—and post your unedited words right on Amazon and call it a book, well, anyone can be an author. So I was looking up books with the terms “Bible” and “America” on Amazon when I came up with Donald Trump in the Bible Code. I found the self-designed cover frightening, and the sentiments expressed in the description grounds for terror. Then I noticed it was only 15 pages long. I’ve written student evaluations that were longer than that.

At three bucks, that’s—wait while I get my calculator—twenty cents a page. Now anyone who’s been able to read the original Bible Code and not cover a snicker or two will possibly find such a jeremiad palatable. After all, it’s a book! Somebody published it. Well, actually, all you need for self-publishing is an internet connection and at least one finger to type and click. Or a toe. You too can become an expert! No education required. Publishing fiction in such a format is one thing, but when people can’t tell a prestige publisher from a vanity press when it comes to factual material, we’re all in trouble.

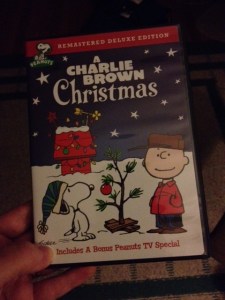

There’s an old saying: “those who can’t do, teach.” I think I first came across this wisdom in a Peanuts cartoon, with all the gravitas that such implies. Editors, it seems, are not required for publishing. In fact, some of us who live by the word seem destined to die by the word. Even with connections I have trouble getting my ideas published. More than once I’ve lingered on Amazon’s CreateSpace page with my finger hovering over the mouse. Publication is one click away and some people make six digits a year publishing only on Amazon. Since I produce about 145,000 words a year on this blog alone (apart from my other writing), the urge is very strong at times. Then I look at that cover and I stay my finger as it hovers. I’ll wait a little longer. At least until November.