Twice in a week. I heard (actually read) a term I’d never encountered before. It’s one of those rare beasts—an “academic meme.” It means nothing to most normal citizens, but it has already achieved currency in academia and on various web platforms. What is it? “Reviewer 2.” Or “Reader 2.” If that means nothing to you, you’re normal. If you wonder, however, what this is about, read on. (Since my posts average two readers, it seems, this is an appropriate topic.) When universities and/or editors do their jobs, they rely on peer review. The idea is simple enough—two recognized experts (sometimes three or more) are asked to read a dissertation, an article, or a proposed book. They then provide their opinion. “Reader 2” (or “Reviewer 2”) has become shorthand for the one that torpedos a project.

Getting academics to agree on anything is like the proverbial herding of cats. Academics tend to be free thinkers and strongly individualized. (Perhaps neurodivergent.) I know from my nearly fifteen years of experience that the most common results when you have two reviewers is two different opinions. Often polar opposite ones at that. One suggestion for the origin of “Reader 2” is that some editors, or dissertation committees, wanting to spare an author’s feelings, put the positive review first, followed by dreaded “Reader 2.” Others suggest that it’s just a meme and that over time (internet speed) the meme came to mean “Reviewer 2” was harsh and mean spirited. The thing is, once a meme is out there it’s difficult to stop. Now, apparently, a generation has made “Reader 2,” well, a thing.

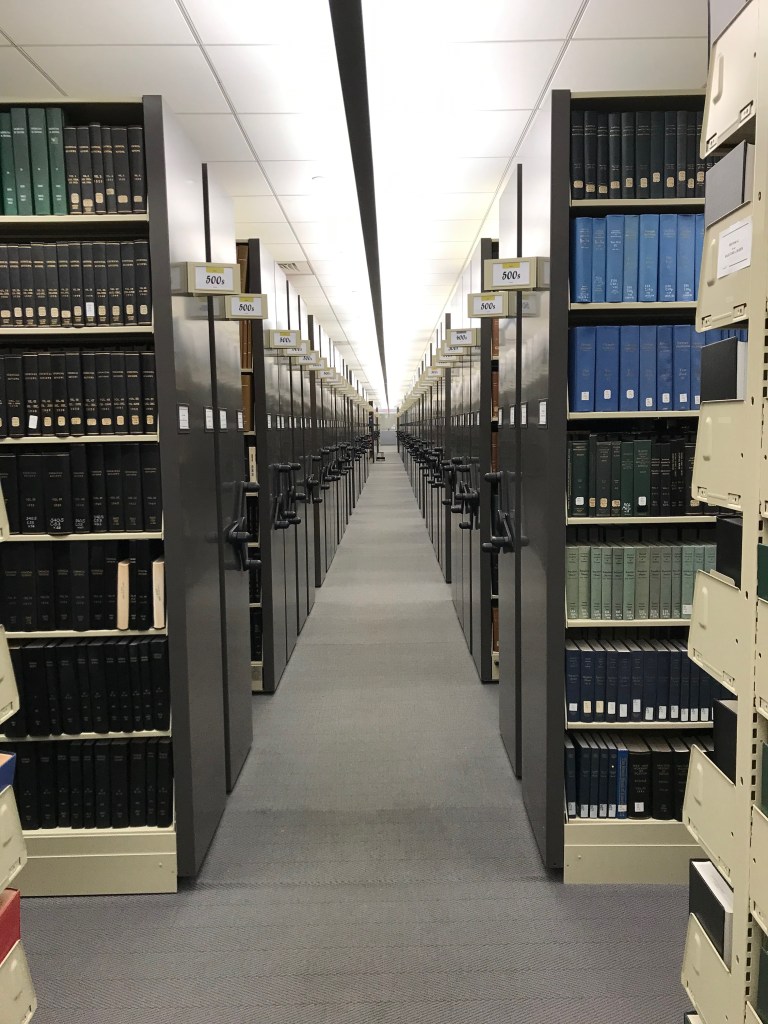

This has been floating around for a while, apparently. I only heard it recently and it occurred to me that I’m missing out in the new academia mystique that the internet has created. My most popular YouTube video is one I did on “dark academia.” I wasn’t aware this is a hot topic among the internet generation. There is a good dose of the unknown regarding what goes on within those ivory towers where the majority of people never go. My own experience of academia was gothic, as I explain in that video. I have a follow-up ready to record, but outside academe finding time with a 9-2-5 and a lawn that needs mowing and weeds that just won’t stop growing, well, that’s my excuse. Whether it’s valid or not will depend upon your assessment, my two readers.