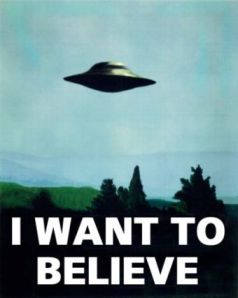

The Flying Spaghetti Monster came onto my radar while teaching at the University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh. I was teaching a course entitled The Bible and Current Events and the controversy over teaching Intelligent Design had been gaining steam. As I addressed the evolution section of the course, I became aware of the Flying Spaghetti Monster and his noodly appendages. The Jesus fish had recently evolved to a Darwin fish, and the Darwin fish was being eaten by a Jesus shark, then I finally saw the Flying Spaghetti Monster on somebody’s bumper. I looked it up online and discovered a whole mythology had been developed to go with this parody of a religion. It was lighthearted and funny and had an obvious purpose—to challenge the equally bogus claims that creationism is science. Now, I don’t try to change anyone’s religion. If someone finds creationism comforting, well, the United States is based on freedom of religion and who am I to dictate what someone else believes? The problem is creationists often don’t share that courtesy and try to get their religion taught in public schools as science, which it isn’t. The Flying Spaghetti Monster was their nemesis.

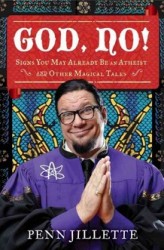

Over the weekend, when I actually have time to do a little surfing, I came across the United Church of Bacon. Noticing the similar food-based theme as the Flying Spaghetti Monster, I decided to check it out. It seems to have become a cottage (cheese?) industry to start your own anti-religion. A look at the United Church of Bacon’s website reveals it to be the brainchild of Penn Jillette of Penn and Teller, and friends. As usual, the voice of Teller is not heard. This is a legal church which performs many of the services of traditional religions, but without the belief. Bacon, it seems, is the ultimate reality here—to quote the church on a billboard: “Because bacon is real.” They have nine bacon commandments and an impressive list of charitable works.

Looking over all of this material, I wonder what the mainstream churches might take away from all of it. For one thing, the obsession that Christian denominations have had for centuries with correct belief has become a kind of albatross. Petty differences in theology tend to lead to hatred in the name of the prince of peace. Another is the repeated emphasis on giving has taken its toll. The United Church of Bacon openly advertises that they give money, they don’t take it. While few clergy become fantastically wealthy, it is no surprise that most bishops or those of equal rank never seem to go hungry or drive cheap cars. If entertainers are rich, it is because they offer something worth paying for. And for those of us who are vegetarians, the UCB offers the alternative of praising vegetarian bacon. You are, after all, what you believe.