Oil City Junior High School. Ninth grade. As a kid who grew up politically naive, Mr. Baker’s words felt like the Gospel. “People will never elect a president against their own economic interests,” he once said. Then came the Reagan years with “trickle down” bs, and, let’s be honest, the working class has been hurting ever since. Reading the political headlines, I’m frankly distressed that politicians no longer have any clear idea what working class life is like. Online I see working-class friends following, zombie-like, the richest man to ever run for President, daily proving Mr. Baker wrong. I’m not naive enough to think that most career politicians of either party know what it’s like to struggle for a living, but I have seen time and time again the Democratic Party trying to stretch out safety nets for those who receive no trickle down hand-outs. I do know what it is to struggle, and I do know that getting an education does not equate to getting a job. I also know that no Republican since Eisenhower has tried to be fair to the working class.

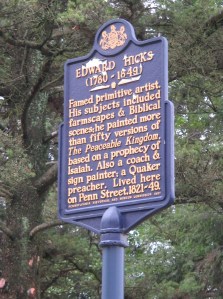

I grew up just outside Oil City, Pennsylvania. It was a town founded by potential millionaires because petroleum had been discovered in the region. Many get-rich-quick schemers settled these pleasant hills and valleys, but the oil pools were as shallow as a politician’s sympathy, and some of the towns in the region became ghost towns. The Oil City I knew was working class families, trying to get by; many grasping religion when politics never ceased to disappoint. We were children of Damocles. Somehow the message has morphed from when I was a child paying attention in school. The issue is now, “I’m not well off, but I sure as heck don’t want the government helping those worse off than me!” Trickle down indeed. To me it seems obvious why the wealthy skew “pro-life”—their schemes cannot succeed without a constant stream of desperate workers. Keep those kids coming!

Because as a child I read all the time, I knew there was a life outside Oil City. Paying my own way through college with crippling debts, I managed to get out and earn an advanced degree overseas, just to be fired by a Republican who thought my advocacy for fair treatment had no place in a seminary. Yes, I’ve felt the barbed lash of unemployment. I spent years wondering what might become of my small family as trickle-downs began defying gravity and wormed their way back up to the wealthy. I’ve never owned a house; none has ever trickled down to my income level. Those Oil City millionaires never gave me any handouts. But Oil City did give me an education. I learned to see through those who say they are protecting me and my future. The only thing they are protecting is securely tucked into their back pockets. I’ve seen their ads castigating Jimmy Carter, a president who is actually out there building houses for the poor. I’ve heard them blaming Obama for not filling in a trench that took Bush the Less eight years to dig. I say let’s just let trickle-down fill that hole. I’m sure the Oil City millionaires will be glad to kick in a greenback or two; after all no one ever votes against their own economic self-interest.