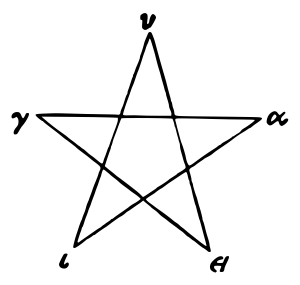

One of the coveted symbols of approval in my childhood was the star at the top of a paper. I watched in amazement (perhaps because they were so rare) when a teacher would inscribe a star without lifting her pencil from the paper. I thought I had never seen anything so perfectly formed. Of course, in my teenage years under the influence of Jack T. Chick and his ilk, I learned that the five-pointed star, especially in a circle, and more especially upside-down in a circle, was a satanic symbol. My childhood achievements had been, apparently, a demonic blunder. This fear of geometry still persists in America, as a story of a woman in Tennessee fighting to have “pentagrams” removed from school buses shows. The woman, who has received death threats and therefor remains anonymous, took a picture of the offending LEDs and has asked, out of religious fairness, to have the satanic symbols removed from the bus. The news reports are almost as tragi-comic as the complaint.

The pentagram, or pentacle, has a long history, some suggest going back to the Mesopotamians. (Uh-oh! We know how they loved their magic!) In fact, the symbol was benign in religious terms until it was adopted by Christians as symbolic of the “five wounds” (zounds!) of Christ. The symbol could also be used for virtue or other wholesome meanings. The development of Wicca began in earnest only last century, although it has earlier roots. Some late Medieval occultists saw the star as a magic symbol, and the inverted pentagram was first called a symbol of “evil” in the late 1800s. As a newish religion seeking symbols to represent its virtues, Wicca adopted the pentagram and some conservative Christian groups began to argue it was satanic, representing a goat head. (The capital A represents an ox head, so there may be something to this goat. I’m not sure why goats are evil, however.) Wicca, however, is not Satanism, and is certainly not wicked.

Symbols, it is sometimes difficult to remember, have no inherent meaning. Crosses may be seen in some telephone poles and in any architectural feature that requires right angles. The swastika was a sacred symbol among various Indian religions, long before being usurped by the Nazis. And the pentagram was claimed by various religions, including Christianity, long before it was declared dangerous by some Christian groups. There may be a coven in Tennessee seeking to covert children by designing and installing taillights of school buses, but I rather doubt it. School children feel about their buses as I feel about mine on a long commute to work each day. A kind of necessary evil. The truly satanic part, I suspect just about every day, is the commute itself. There must be easier ways to win converts.