A friend recently introduced me to the YouTube channel, Cinema Therapy. While I had some vague notions already that cinema therapy was “a thing,” I had never looked into it. This was so, even while consciously knowing that I use movies that way. Most of what I’ve seen on the YouTube channel has been about Disney/Pixar movies, especially those that tug at emotions. These have never been my favorite movies since I have unresolved issues from childhood. Still I learn a lot from watching their analyses. It can still be difficult to watch these films, though. As a family we recently rewatched Finding Nemo. It struck me pretty hard how growing up without a father figure left me the anxious, quivering mess that I often am. I prefer movies where I can find a father, no matter how odd the choices may be.

In fact, in my own form of cinema therapy, I use horror films. (Even the YouTube channel parses M. Night Shyamalan.) Part of this is clearly because such movies take me back to my childhood. I’m not sure why I found monsters so comforting, but I did. We had no father and I latched onto the strong men—particularly if they didn’t smoke or drink—that dominated movies (it was the sixties, after all). Somehow I felt that this made the world seem alright. Or a little less scary. I didn’t understand the biology of parenthood, I just knew that I needed a man in the family. One who would protect me and show me how to be a man. Well, that never really happened. My step-father was verbally abusive and I seemed to be his special target. I watched horror and listened to Alice Cooper.

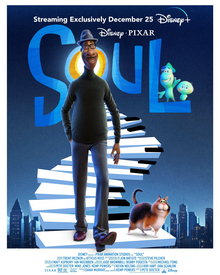

Sublimation, in psychology, is where you put difficult feelings aside, acting as if everything’s normal. I did that for many, many years. College, seminary, doctoral program, full-time professorate. Then it all broke down. After the tragedy at Nashotah House, I found myself watching horror movies again. It took about a decade of doing that to realize that I could write books about the connection between religion and horror. With three published (the third about to be, actually), I have a fourth nearly finished. The writing is therapeutic as well. I have to wonder, however, if these Pixar movies that are so painful for me to watch are really helping me. I don’t always feel refreshed afterwards, as I do when I see a good horror movie. (Bad films are their own kind of therapy.) I’m an amateur psychologist (no license), with a most intractable client (myself). My way of dealing with him is to watch horror and call it therapy.