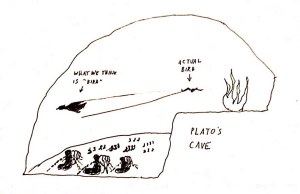

The conversation began, as conversations often do, with Plato’s allegory of the cave. The nature of reality was the topic of a chat I had with a very intelligent undergrad the other day. Plato believed in a realm of ideal forms. What we experience in life is not the actual forms themselves, but a reflection of them sufficient to alert us to what it is we encounter. Humans are sitting, as it were, in a cave. We are chained so that we face the inside wall of the cave and can’t look around. Behind us there is a fire and the ideal forms pass between the fire and people, throwing their shadows on the wall. Not having ever been outside the cave, we suppose the shadows are reality. We are, however, deceived. This led, naturally enough, to a discussion of Aristotle’s counter-argument that the “essence,” or entelechy, of things is something inherently within it. No need for an alternate realm of reality. And so, I asked, what is reality? What is truth?

My young interlocutor said that reality is what we perceive. It is different for every person, and therefore there are a multitude of realities. Truth is simply the term we apply to our experience of reality. I began to feel as old as Plato. When I was young I believed, not exactly in a realm of ideal forms, but in a universe that contained abstracts. Abstract concepts objectively existed, and in a kind of neo-Platonism, we recognized them when we encountered them. Love, for instance. We may not be able to define it precisely (although materialists claim it is just a pretense to get sex), but we sure know it when we feel it. Or consciousness. What is it? No one reading this doubts, however, that it exists. And truth. I had always assumed that there was Truth with a capital T, objectively floating around out there. Perhaps, if the undergrad is right, there are multiple truths around. We chose the one that fits our experience of reality. Q.E.D.

C.Q.D.! C.Q.D.! Worldviews are in the process of changing. I tend to think the internet has democratized truth. Religions have tended to play their trump card—revelation—at this point. The unambiguous input from the divine should end all questions. But it only requires a moment’s reflection to realize that there are multiple religions and multiple revelations. Which one are we to believe? Some scientists claim there is no need for philosophy, religion, or the humanities. Objective facts, however, are interpreted subjectively. To privilege one reality above others is a kind of intellectual fascism. Perhaps my reality is different. We all sit in the same cave watching the same shadows play in front of us. We then decide what is real. Perhaps we need to get outside for a breath of fresh air. Even Plato knew, however, that that is against the rules.