I’ve seen The Post before. Maybe it took recovering from a vaccine to make me realize, however, just how much we’ve lost with the rise of electronic publication. Yes, there is now a shot at recognition by the lowliest of us, but publication used to mean something important. Consider how Watergate, the coda to the film, brought down Nixon. Now we have a president who could’ve never been elected without the world of the internet, and who is coated with teflon so thick that even molesting children can’t harm him. I work in publishing these days. I often reflect on how important it used to be. Ideas simply couldn’t spread very far without publication. That’s what makes The Post such an important movie. It’s the story of how the Washington Post came to publish The Pentagon Papers. Said papers revealed that the United States was well aware that the Vietnam War was unwinnable, even as the government sent more and more young men to their deaths.

There are many ways to approach this film, including the doubt that it instills in even free democracy, but what struck me as the vaccine was wearing off is how publication has become a more challenging and endangered as the Wild West of the internet continues to expand. Newspapers used to be the harbingers of truth. Early in the history of the broadsheet, however, there were those who’d make things up in order to sell copies. (Capitalism is always lurking when skulduggery is afoot.) Over time, however, certain papers gained a hard-earned reputation for reliable reporting and publication with integrity. A story going out in the early seventies in the Washington Post could influence history. Now it’s owned by Jeff Bezos.

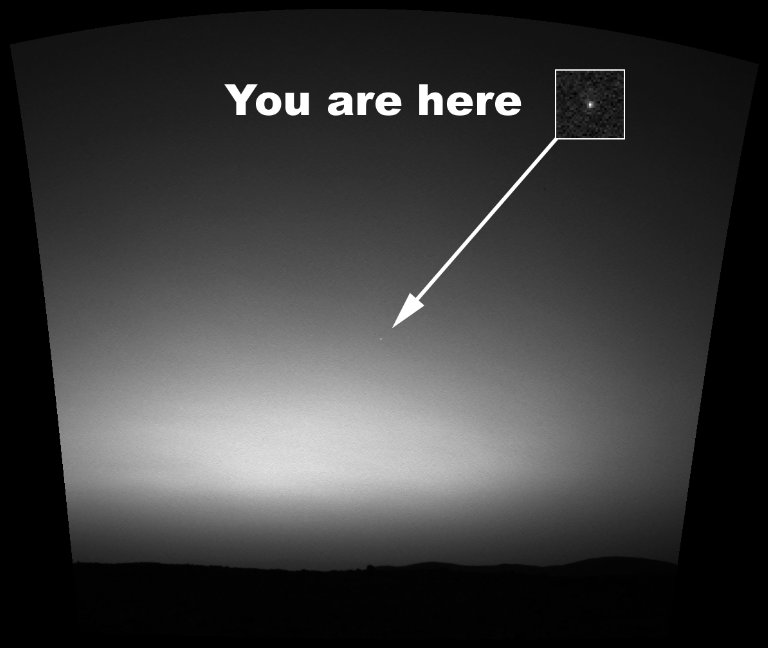

There was a time when a book might change the world. Now there’s a little too much competition. Publishers of print material struggle against the free, easy access of the internet. All that publishers really have to offer is their reputation. Those that have been around for a long time have earned, the hard way—you might say “old school”, the right to tell the world the truth. Now the truth comes through Twitter, or X, or whatever it’s called these days and more often than not consists of lies. Of course I don’t believe the internet is all bad. I wouldn’t contribute daily content to it if I believed that. Still, I fear we’ve lost something. Something important. And right now we have nothing to replace it.