What more is there to say about God and politics? Far too much, I fear. In a Sunday Review in the New York Times, Frank Bruni lays out a catalogue of what, in a rational universe, would be considered violations of the United States constitution by politicians who insist their (conservative) Christianity is the faith of the nation. This is, however, one of the philosophical conundrums of religious freedom. Religious believers are free to use their faith to try to change the system from within. And the fact that the media is telling us that religion has become irrelevant doesn’t help. Who should be afraid of what’s irrelevant? Can irrelevant substances harm you? Can irrelevant bullets kill you? Why, yes, they can! And so being told repeatedly by the media that religion is something we can safely lock into a box marked “Medievalisms Outdated” we step out the door to see politicians using a religion poorly understood to gain power. A recipe for an apocalypse, it sounds like to me.

Academics too readily fall prey to the media hype. University presidents and deans suppose that religion really is dead and shouldn’t be studied. Who’s going to help us through the morass of the upcoming election if people who understand religion are made indigent and put out on the streets? Good luck to the rest of society! We must, if we are to survive, understand religion. Its death, following shortly on that of God, was proclaimed early last century. And yet it’s showing no signs of dying. In fact, it’s just waking up. Who are we going to ask? Scientists? Accountants? Economists? What will you really learn about our laws being God’s laws in the minds of the wealthy and powerful? Don’t ask me—I’ve only spent some thirty-five years studying religion. What do I know?

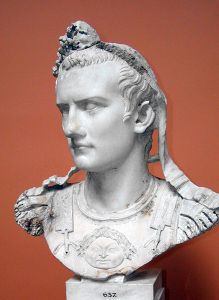

I sometimes wonder what it must’ve been like to live in Rome as Alaric was whetting his sword among his Visigothic horde. Insane—literally insane—emperors wielded unchallenged power and lived lives of opulence amid the slaves and poor. Religion was front and center on the agenda, of course, because emperors were gods. You don’t have to listen too deeply to hear the same message even today. Those who proclaim God as the justification for their political ambitions know that God is the ultimate malleable deity. In fact, God can even be in the Oval Office. Lead can line your aqueducts and your horse can be made a senator. Lord knows an ass can be. And all the while let’s shut down the voices of those who’ve looked at religion, beginning in the Stone Age and up to now. If we want to grab power it’s vital that we keep it from public view that self-deification is as old as kingship and in a post-religious world, we have only to pretend.