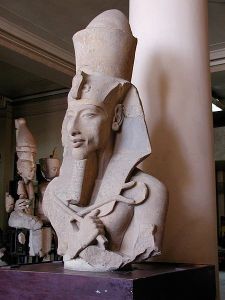

Those of us who write know all about revising. You go back to a piece you wrote, maybe even just days ago, and you see all the things you want to change. Corrections, improvements, deletions, retractions. Histories are particularly prone to being viewed in new ways with the passing of time. I once thought histories were factually true, but in this postmodern age we’ve learned that while histories contain some facts, they are largely interpretations of those facts. Even the Gospels are interpretations. Recently I’ve been reading about student movements wanting to efface some facts of history because they make current-day people feel bad. A piece in The Guardian, for example, explains how some students want to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes from Oriel College, Oxford, because Rhodes was an imperialist and a racist. A similar movement is afoot at Princeton University to give Woodrow Wilson the old Akhenaton treatment for similar reasons. Student interest groups, as The Guardian points out, don’t want to be reminded of their once marginal status. Removing Rhodes (or Wilson) from his pedestal, however, won’t change history.

Those of us who write know all about revising. You go back to a piece you wrote, maybe even just days ago, and you see all the things you want to change. Corrections, improvements, deletions, retractions. Histories are particularly prone to being viewed in new ways with the passing of time. I once thought histories were factually true, but in this postmodern age we’ve learned that while histories contain some facts, they are largely interpretations of those facts. Even the Gospels are interpretations. Recently I’ve been reading about student movements wanting to efface some facts of history because they make current-day people feel bad. A piece in The Guardian, for example, explains how some students want to remove the statue of Cecil Rhodes from Oriel College, Oxford, because Rhodes was an imperialist and a racist. A similar movement is afoot at Princeton University to give Woodrow Wilson the old Akhenaton treatment for similar reasons. Student interest groups, as The Guardian points out, don’t want to be reminded of their once marginal status. Removing Rhodes (or Wilson) from his pedestal, however, won’t change history.

I wonder if those in these special interest groups have enough experience to realize the implications of their complaints. What if, for the sake of argument, one of these student leaders became a national leader? What if her (or his) nation became oppressive during her or his lifetime but s/he didn’t see it because it was the operating milieu of the age? And what if their nation later repented and brought those from their former oppressed colonies to their homeland and those who came turned against that past leader? The point of this scenario is to suggest that none of us—or at least very few of us—have the ability to think beyond our age. Can we be blamed for being children of our time? Will removing our mementos change the facts of history that will have transpired? Will it make us feel better to bury the truth of what happened?

An issue that often weighs upon my mind when I hear of these groups of the marginalized is that there is a very large, and very diverse marginalized class that has no voice, even today. The poor. Sure, some of us raised in poverty can claw our way to a descent living, but succeeding in a world where you need connections and favors owed and special knowledge of how a system works will be forever beyond our grasp. I knew a refugee, once upon a time, who was a student of mine. He used to complain to me of the costs of having his shirts sent out to be laundered. His clothes were tailor made. He refused to use a washing machine. He was also quick to point out that I was the oppressive race. This he did without a nanogram of irony. Cecil Rhodes may have been as evil as some say he was. His money, however, made it possible for some of the heirs to his oppression to study in his shadow. And I write that with a heavy dose of irony. Do they not realize that Akhenaton is now considered by many to be the most interesting Pharaoh of them all because he was erased from history?