Realizations dawn slowly sometimes. From childhood on I wanted to be a writer. Teachers encouraged me because I seemed to have some talent, but in a small town they didn’t really know how to break through. Besides, terrified of Hell, I was very Bible and church focused—not really conducive to the worldliness needed to be a writer. The realization that recently dawned is that I’m competing with people who can put full-time into writing. I’m trying to squeeze it into a couple hours before dawn every day because 9-2-5. 9-2-5. 9-2-5. It’s exhausting. I often read about writers, wondering how they get noticed. Even the people I try to get to publish my fiction read stuff others likely have more time to write than I do. Why do I keep at it? Sometimes it’s just impossible to keep ideas inside.

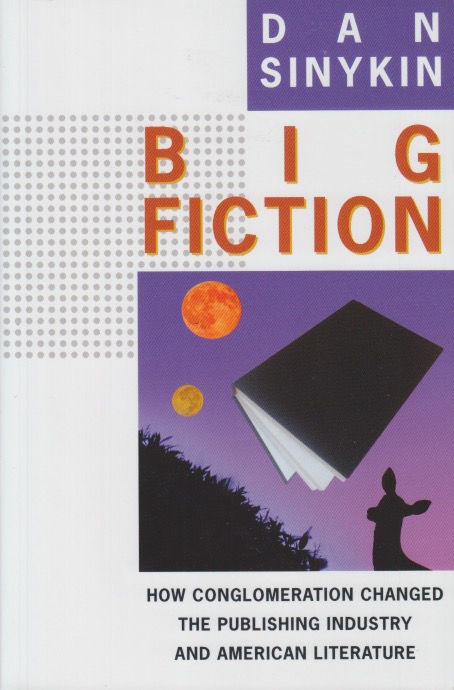

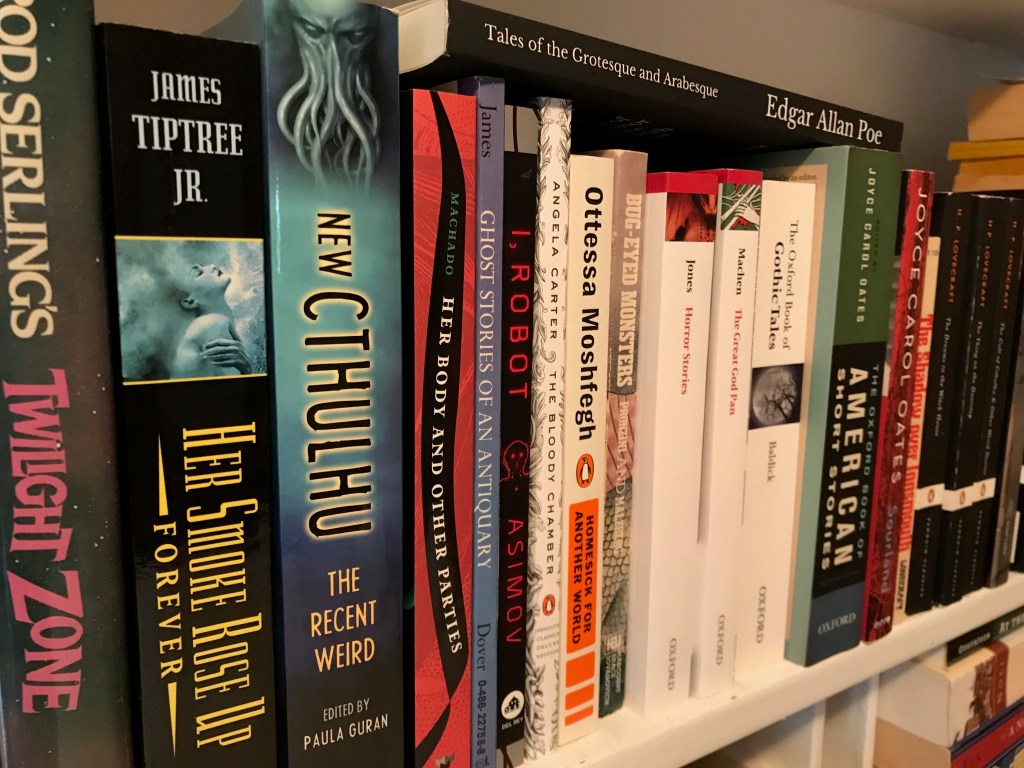

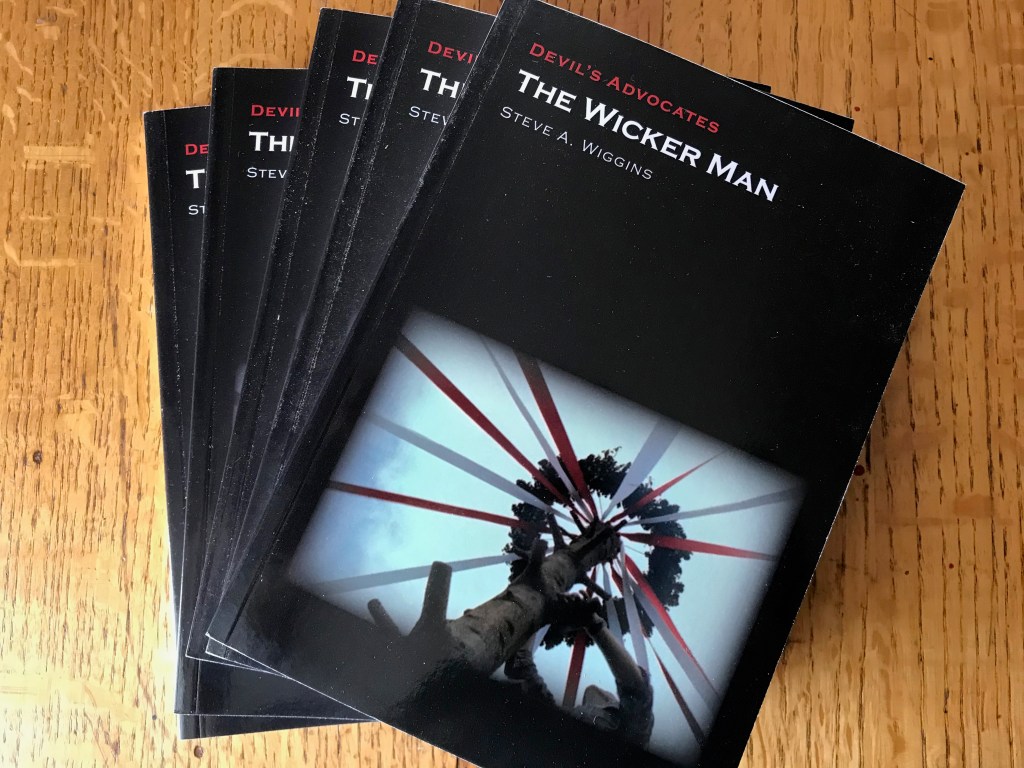

I’ve got ideas. Some of them would make fascinating movies. I even had an editor of an online journal that published one of my stories say that. I’ve got a cinematic imagination trapped in the aging body of a day-worker. Oh, I’ve got a professional job, of course. What I really want to do is “produce content.” I know others in publishing with the same dream. One of my colleagues has managed to break out and she’s now publishing novels that are getting noticed. I’m still writing for academic presses because I know how to get published by them. My fiction has been suffering from neglect. To stay sharp you have to keep at it. I’m a self-taught writer. I’ve not taken a course in it my entire life, and it probably shows. Not even Comp 101.

Fairness is a human construct and ideal. Reality lies with Fortuna (cue Carl Orff). I’m better off than most people in the long human struggle with equity, I realize. For that I’m grateful. I do have to wonder, however, if struggle isn’t essential to making us what we need to be. The writers whose work endures often had to struggle to get noticed. Many died in obscurity. I wonder if they ever realized that they were leaving a legacy. You see, writing is a strange blend of arrogance and self-doubt. Many of us go through intensely self-critical times when even our published books seem to mock us from their shelves. The realization, now fully day, that I will always have to struggle to do what I know I’m meant to do sheds light. Even in the world of privilege, the struggle inside is real.