Here’s a public service announcement for your Friday. If you’ve been wanting to read Holy Horror but found the price too high, McFarland has now lowered the cover price to under $30. Here’s the link: Holy Horror. Of my non-academic books, this has been my “best seller.” Since I’m currently shopping around another book, and since agents aren’t interested (at least not any more), I wondered whether McFarland might look at it. The editor who handled Holy Horror had left, and the new editor responded to my concern about pricing by telling me that they lower prices after a couple of years. She noticed, however, that Holy Horror had been overlooked in the price lowering process, so voila! It’s now affordable.

This model, while not the same as trade publishing’s efforts to get primarily front-list sales, seems to make sense. Too many publishers raise prices year after year, so if you don’t buy immediately you’ll pay more. McFarland tends toward a paperback first model. The first couple of years are aimed at library sales—and they do well at those—then they lower for individual purchase. All I had to do was ask. Two years ago I asked Lexington/Fortress Academic if they’d do a paperback of Nightmares with the Bible. That poor book never had a chance. The editor said they were considering it. Instead they did the trick that publishers seem to like: decoupling the ebook price from the hardcover. So you can buy some expensive electrons instead of holding a real book. So it goes. I’ve written a museum piece.

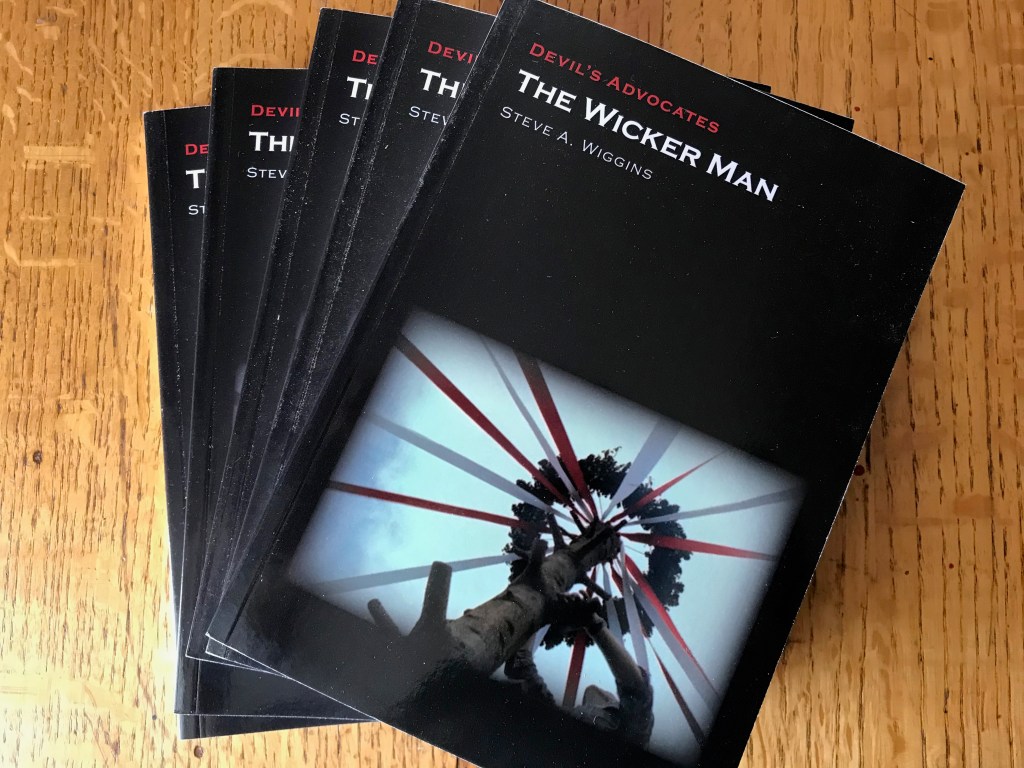

It’s a little too soon to say about The Wicker Man. My experience has been that university presses, particularly British ones, like to raise prices rather than chasing sales. If you’re reading this blog you know that I’ll market my books. I even printed bookmarks for Holy Horror at my own expense. Maybe it’s time to start distributing them again. What a difference ten dollars can make! I’m a book booster. (You might not have noticed.) I’m glad that McFarland understands that individuals will buy books, even if they’ve been out for a while. The standard wisdom among academic publishers is “three years and then you’re done.” If you’re inclined to help prove that business model wrong, you can now get Holy Horror without having to take out a second mortgage. That’s cause for hope—any writer has the dream that her or his book will keep on selling. Sharing this information will, it seems, make it wider known. Please pass it on.