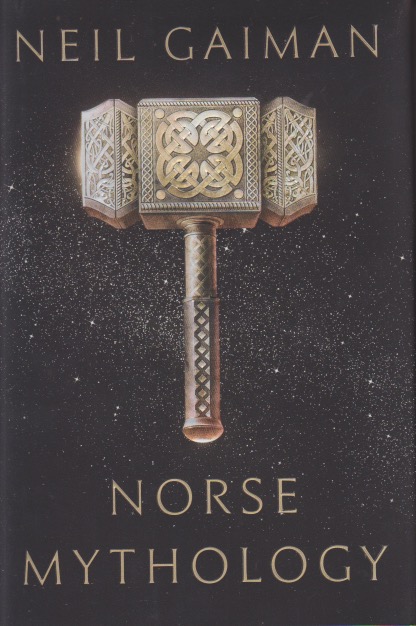

As organized religion continues its slow decline, mythology remains. Indeed, it seems to be growing in interest. The problem with many mythologies, for monolinguals, is that they come in languages other than English. Translation always loses something, which is why, I suspect, Neil Gaiman was tapped to retell the Norse myths. A very talented story-teller, Gaiman has written about gods before. He knows their literary potential. Norse mythology is rather odd in the canon of western thought. The stories feature gods with as many foibles as humans and with conflicting motivations. In some ways they are more believable than the monotheistic tradition. They are both fun to read and poignant.

At the same time Norse Mythology is a somewhat perplexing book. It’s difficult to tell, without being an expert, what is Gaiman and what is ancient. In fact, the book sits next to another one with the exact same title on my shelf. That one is labeled nonfiction, and it’s a bit more academic. Perhaps it’s an occupational hazard that I tend to want to approach mythology in original languages, if possible. I’ve never studied Nordic tongues and it would be a little difficult to justify starting now, with all the other things I’ve got to do. It’s not that I don’t trust Gaiman, it’s just that every retelling is an interpretation. Still, I’m sure the book gives the flavor of the records that survive. One of the fascinating features of Norse mythology is that gods die. Since it ends with Ragnarok, that seems inevitable.

Many mythologies have the world ending with the establishment of the happy reign of a singular deity. Ragnarok, which Gaiman (and perhaps the originals) sets in the past, sees the gods dying on the battlefield against Loki and the giants. As the earlier myths make clear, however, death in battle is the most glorious way for the Norse to end their lives. (And seeing how it has led to a pretty peaceful adult nation, one wonders if the mythology had a calming effect.) I’ve not read extensively in other versions of Norse mythology so I don’t know if Gaiman’s ending with Balder returning and the world starting anew is his innovation or part of the original. Having gods who die, however, seems like a potential leveler for humans who suffer from greater powers. There’s a sobriety to it that lends gravitas to the whole. And like all good books, Norse Mythology has left me hungry for learning more.