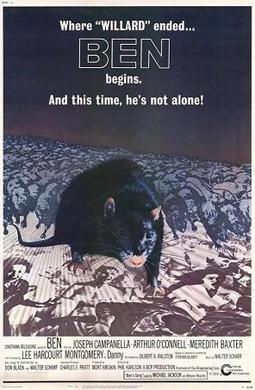

I’ve asked other survivors of the 1970s if they knew that the Michael Jackson hit “Ben” (his first solo number one recording) was written about a rat. Most had no idea. The song is the theme for the sequel to Willard, namely, Ben. Now, I have a soft spot for seventies horror movies. Before the days of streaming I repeatedly looked for Willard in DVD stores and never did find it. I eventually found it on a streaming service and even wrote a Horror Homeroom piece on it. One winter’s weekend with not much going on, I finally got around to seeing Ben. Neither are great movies, but I’ll give them this—people in my small hometown knew about them. Everyone I grew up around knew that “Ben” was a song from a horror movie. In case you’re part of the majority, Ben is the chief of the intelligent rats who turns on Willard at the end of his movie.

An incompetent police department and other civil authorities can’t seem to figure out how to exterminate rats when they begin attacking people. A little boy, Danny, has no friends. He is apparently from an upper-middle class family, and he has a heart condition. Ben finds him and the two become friends. Danny tries to get Ben to lead his “millions” of rats away from a coming onslaught, but for some reason Ben decides to stick around and nearly get killed. In the end, badly injured, Ben finds his way back to Danny. Cue Michael Jackson. It really isn’t that great of a movie—the number of scenes reused during the tedious combat scene alone belies the pacing of a good horror flick. I felt that I should see it for the sake of completion. Check that box off.

It’s a strange movie that ends up with viewers feeling bad for the rats. They’re not evil, just hungry. They do kill a few people (poor actors, mostly) but it’s often in self defense. The best part is really the song, and the premise behind it—boy meets rat, boy falls in love with rat; you know how it goes. Michael Jackson famously loved horror movies, and as many of us have come to realize there’s not much not to like. This movie is pretty cheesy (with the rats attacking a cheese shop, but only after an unintentionally hilarious spa scene) but it has heart. And it has a fair bit of nostalgia for those of us who grew up in the seventies.