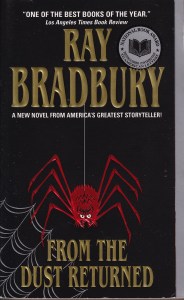

The fiction author who had the most influence over my formative years was Ray Bradbury. Wait—let me qualify that a bit. I read of number of series aimed at juvenile, male interest (Doc Savage, Dark Shadows, and such) but these weren’t really intended as “literature.” I also read quite a bit of Poe, and his influence may certainly have rivaled Bradbury. The thing was the latter was still alive and producing books, mostly of short stories that tickled my imagination. Despite my reluctance to let books go, there have been several periods in my life where I’ve had to sell off my collection (this is the mindset of the non-affluent) and all of these childhood collections went, except for Poe. Now that I’m a more reflective adult, so I’m told, I have found a renewed interest in some childhood classics, and Ray Bradbury books are seldom expensive. When I found From the Dust Returned in a used book shop for a steal, I said “why not?”

The fiction author who had the most influence over my formative years was Ray Bradbury. Wait—let me qualify that a bit. I read of number of series aimed at juvenile, male interest (Doc Savage, Dark Shadows, and such) but these weren’t really intended as “literature.” I also read quite a bit of Poe, and his influence may certainly have rivaled Bradbury. The thing was the latter was still alive and producing books, mostly of short stories that tickled my imagination. Despite my reluctance to let books go, there have been several periods in my life where I’ve had to sell off my collection (this is the mindset of the non-affluent) and all of these childhood collections went, except for Poe. Now that I’m a more reflective adult, so I’m told, I have found a renewed interest in some childhood classics, and Ray Bradbury books are seldom expensive. When I found From the Dust Returned in a used book shop for a steal, I said “why not?”

This particular book came from long after I’d sold my Bradbury collection. I had never seen nor heard of it before. As an adult, interestingly, Bradbury doesn’t seem scary at all. From the Dust Returned, like many other Bradbury collections, is a somewhat novelized set of stories. This one is set in a haunted house where, in his usual descriptive style the storyteller offers artful prose and painterly writing, but no real scares. As we are coming upon Banned Book Week, however, I did note one of Bradbury’s common themes—the lack of belief leads to the death of characters. I’d read some of his stories where this took place before. Still, this time he goes a bit further. Tapping into things just ahead of the rest of us, as he had a talent for doing, one of his characters laments the loss of belief in religion as well as creepy, Addams-esque characters. People are no longer believing and it causes ghosts pain.

Part of Bradbury’s appeal is clearly to the young imagination. I’ve promiscuously read hundreds of authors since my last Bradbury book. My tastes have evolved. I find the same is true when I go back to the Dark Shadows books that were so cheaply had at my neighborhood Goodwill. I still go back to these early writers, however, and there is a kind of innocence about them. These were stories I’d read before I’d learned that Poe was certainly not as macabre as real life could be. “Marilyn Ross,” “Kenneth Robeson,” Edgar Allan Poe, and Ray Bradbury may not feature of lists of banned authors. Some of them aren’t even whom they seem to be. They did instill a childlike belief in reading, in my case. Even if they’re now on the bargain shelf they will still receive my admiration for starting a lifetime of reading.