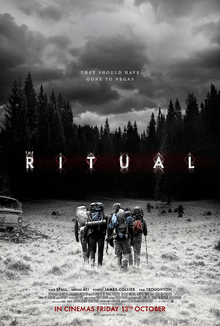

We still fear pagans. Religion and horror are often tied up together, but when it comes to monsters we trust Catholics and fear pagans. Of course, when Startefacts recommended The Ritual it was in the context of five pagan horror movies you should see. I’d seen three of the others, so The Ritual seemed the next logical step. Four friends are hiking through Sweden to honor the wishes of a fifth friend killed during a robbery. When one of the them injures his knee, they decide to take a shortcut through the forest where a combination of the Blair Witch Project and Midsommar and Antlers takes place. After finding a freshly gutted elk in a tree, they take shelter in an abandoned cabin surrounded by runic signs on the trees. Soon they’re being hunted by a huge creature they can’t see clearly.

The final two are captured by a pagan group that worships one of the Jötnar—the monster that’s been hunting them. The final boy escapes by getting out of the forest, where the Jötunn can’t go. The choice of a Germanic monster is a bit different, and the creature design is fascinating. Jötnar apparently straddle the line between gods and monsters, being a kind of frost giant. The pagan group sees it as a deity that keeps them safe in return for sacrifices. Given the number of bodies in the trees, other hikers had decided the shortcut was worth taking in the past. But still, the pagans are cast as the bad guys. This is in spite of the fact that the friend whose death started the whole thing was killed in England.

The religious convictions of the English robbers aren’t made clear, but they were raised in a Christian context and are every bit as brutal as the pagans. In fact, the pagans, although they sacrifice strangers, do try to talk kindly to them (at least if they have the mark of the Jötunn on them). Not just the pagans are savages. At least they have a moral reason for what they’re doing, in their own minds. The criminals are in it only for themselves. We still fear those of other religions, although they’ve come to their beliefs in a way similar to how we’ve come to ours. Whether born into it or converted, believers generally come to their conclusions honestly. In the world of the film, this Jötunn is real. And, until the end, it protects those who worship it. So yes, this is a pagan horror film, but it makes the viewer wonder whence the horror really comes.