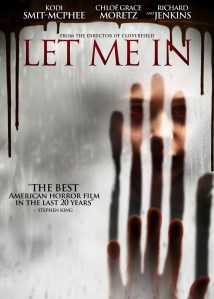

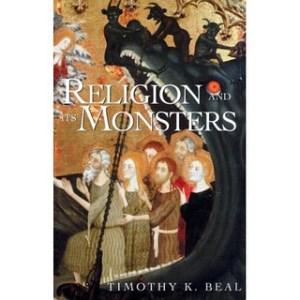

When you’ve got a good thing going, why stop? Reading Timothy Beal’s Religion and its Monsters put me in the mood for a vampire flick over the holiday weekend. I had watched with longing as Matt Reeves’ Let Me In flew into and out of theatres back in 2010. Advertised as a thoughtful vampire story based on John Ajvide Lindqvist’s novel, Let the Right One In, and having a real moral struggle unlike the Twilight saga’s dulled fangs, it had been on my “to see” list for quite some time. This movie doesn’t disappoint. The specific aspect to which I refer, of course, is the religious. Vampires may be the most religious monsters ever invented, and like all good, subversive movies Let Me In casts the religious aspect in an unexpected role. Religion and the vampire interact through the character of Owen’s mother. Her face never seen on the screen, she shuffles outside the range of view and tells her son of the need for prayer and belief. Her life is a shambles and 12-year-old Owen knows it.

Abby, the vampire next door, is a monster capable and desirous of love. Her vampiric self is not exposed to crucifixes or blessed communion wafers, but to the torment of outliving those she loves. Eternal life is her curse, and religion can do nothing to solve it. When Owen slips twenty dollars from his Mom’s purse to buy Abby some candy, Jesus is watching from the mirror. When the bullies torment Owen, Jesus is nowhere to be found. The symbolism, whether intentional or not, is apt social commentary. Our religion is there to punish us, not to help us. If in doubt, listen to the politicians and televangelists; God is intensely angry—Jonathan Edwards wasn’t even halfway there. Their surfeit of rectitude puts the rest of us to shame. Until they’re elected.

Vampires have their origin in creatures that steal the life-essence of the living. Whether blood, semen, or psychic energy, the vampire feasts while the victim withers. Let Me In, by telling the story of a pre-pubescent vampire, shifts the focus of culpability. A 12-year-old is beneath the age of responsibility according to the Judeo-Christian tradition. Unable to determine right from wrong, the child simply seeks what all living creatures do—the possibility of existence. When Owen discovers that his new friend, his only friend, is a vampire, he tries to find answers from his religious mother. She is asleep. He calls his absent father who blames the religion of his mother. The moral guidance here comes from the monster. The bullies would win if it weren’t for what the authorities call evil. Sometimes I think Jonathan Edwards got it all backwards, for when power determines who is righteous it is the bullies who dangle spiders over the fire.