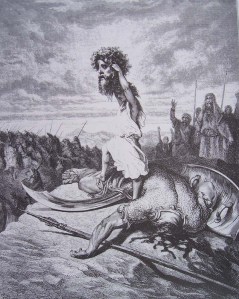

Formulaic to the point of plagiarism at times, 1950s science fiction movies often follow the deeply worn ruts left by countless forgettable monsters. One such film that I managed not to see until recently was the biblically entitled The Giant Behemoth. In a more biblically literate society the poster’s catchphrase “The Biggest Thing Since Creation!” may not have been necessary, even though leviathan’s lesser known companion stole the title this time. Of course the movie begins with stock footage of nuclear explosions, and although I’ve seen such renditions hundreds of times, they remain troubling to the core. Those 1950s that many consider so carefree were days of insidious freewheeling with the environment, days before human infatuation with the power over nature revealed its horrifying consequences. The behemoth, a sign of Yahweh’s great creativity in Job, here becomes the human-wrought agent of destruction.

Formulaic to the point of plagiarism at times, 1950s science fiction movies often follow the deeply worn ruts left by countless forgettable monsters. One such film that I managed not to see until recently was the biblically entitled The Giant Behemoth. In a more biblically literate society the poster’s catchphrase “The Biggest Thing Since Creation!” may not have been necessary, even though leviathan’s lesser known companion stole the title this time. Of course the movie begins with stock footage of nuclear explosions, and although I’ve seen such renditions hundreds of times, they remain troubling to the core. Those 1950s that many consider so carefree were days of insidious freewheeling with the environment, days before human infatuation with the power over nature revealed its horrifying consequences. The behemoth, a sign of Yahweh’s great creativity in Job, here becomes the human-wrought agent of destruction.

Poor Tom Trevethan is blasted by the beast’s radioactive breath in a scene more fitting to Revelation than to Job. In the funeral scene, the priest somewhat insensitively reads a description of behemoth before Tom’s sole surviving family, his daughter Jean. So like the 1950s the minister then declares that the Bible gives comfort to those left behind, when the Lord said to Job, “Gird up thy loins like a man.” Indeed. Loin girding was a masculine activity in the days before Fruit of the Loom had been grown. Comfort for the woman comes in acting like a man. Yes, the 1950s considered the man the default model of human being. It says so in sacred writ. Genesis 3, to be exact.

When the scientists can’t figure out what killed the old man, along with thousands of fish, they ask Jean if her father said anything before he died. She tells them about behemoth. Being scientists, they have no idea what a mythical, biblical creature might be. Jean informs them, “It’s some prophecy from the Bible; it means some sort of great, monstrous beast.” Well, Job is technically not prophecy. Actually it’s not even untechnically prophecy either. In the 1950s, however, if it was biblical, it could be interpreted as prophecy. The real foretelling, though, is clearly atomic. Such films can easily be forgiven their biblical infelicity for the sake of their good intentions of reigning in human self-destructive behavior. In the end science destroys the biblical beast, but I’m left wondering if it isn’t more of a parable than a prophecy. I guess it’s time to gird up my loins and go find out.