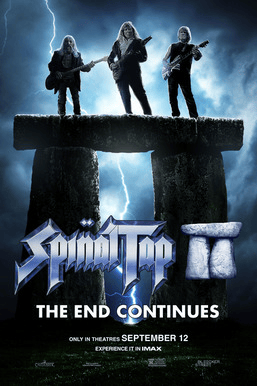

I grew up with rock-n-roll. Those born in the previous decade to mine can say the same thing, but collectively we are the earliest now adults who never knew life without it. Extrapolating from that, the longest surviving early rockers are also aging and many of them are still playing. In a nutshell this was the inspiration for Spinal Tap II, a mockumentary where Tap is legally obligated to perform one more concert. The band members have been estranged for years, each having taken up a different career. As with This Is Spinal Tap, their final concert is being documented by an interested director. The band tries to negotiate all the changes that have taken place since the eighties which, God help me, were forty years ago. The premise is both funny and sad. Tensions still exist between Nigel and David, with Derek being the glue that holds them together.

The movie is entertaining and well done but does lack the energy of the 1984 film. It made me reflective since the nature of fame is no protection against having to work into old age to survive. Rock stars, like athletes, tend to peak at a young age. With the improvements in health care and lifestyle, they can live many years beyond the height of their influence and it’s not unusual, if the money wasn’t managed well, for work to continue. That fact hangs like a pall over the humor. I still listen to the bands and performers from my youth who’ve continued to rock into their seventies, or in the case of the movie, Paul McCartney in his eighties, and ponder the passage of time and what it means. As someone aging myself, I know what it’s like to think like a young person but awake with a body shy on the spryness factor.

Although critics mostly liked Spinal Tap II it did poorly at the box office. I suspect many people my age feel this dilemma keenly. Those of us who are seniors sometimes aren’t willing to let go and let others eclipse us. We see this in the world of politics all the time. Capitalism sets us up so that generally those who are old control the resources, and, rewarding greed, this system doesn’t encourage letting go. Power, I imagine, creates quite a rush. Being on stage with thousands of people adoring you must be something almost impossible to let go. I also listen to some younger artists. Rock is uniquely fitting for the young. To me it seems that all is right as long as the music continues and inspired people, often young, continue to make it.