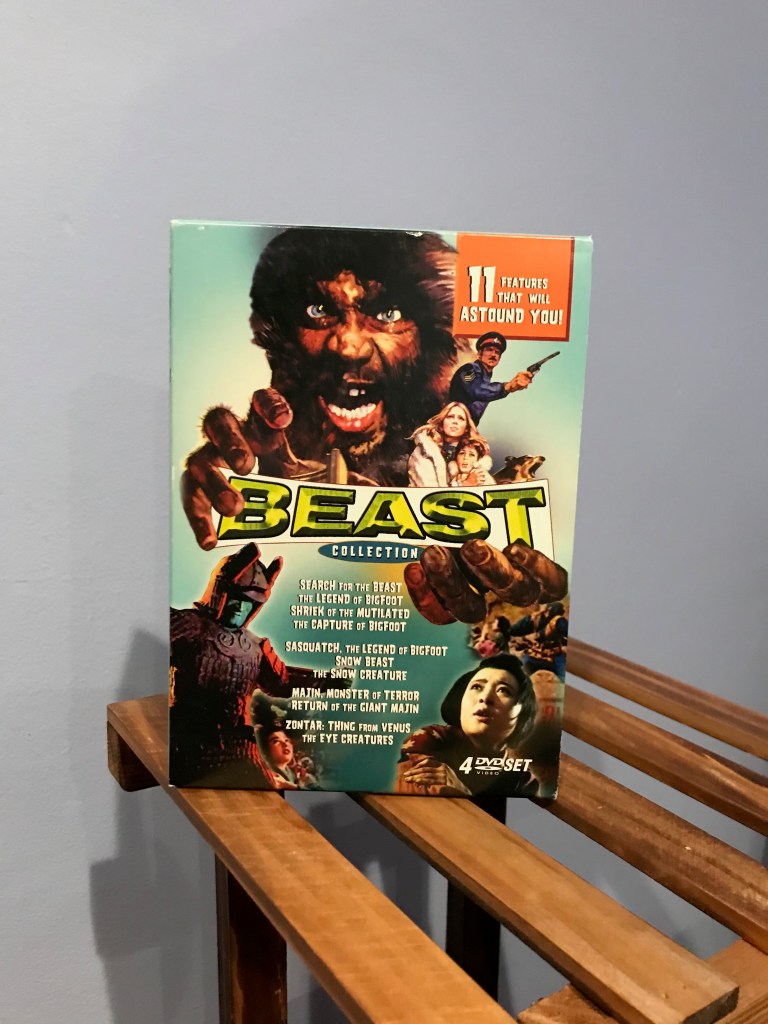

This movie’s so bad there’s a backstory. Years ago I was really wanting to see Zontar: Thing from Venus. This was before streaming, and I found it as part of the “Beast Collection,” a set of 11 movies for less than the price of one regular first-run DVD. I watched a few other movies in the collection, but before long it got shoved to the back of a shelf and forgotten. I remembered it recently because another collection I have was missing a movie, Snow Beast. I wondered if it might be part of this otherwise forgotten set. It was (this really encouraged me because maybe my memory is still much better than I sometimes suppose). In any case, one of the other movies—one I’d never seen—was Search for the Beast. I figured, why not? This is a film that fails on every level. And I mean every single one. It really should merit a Wikipedia page, just for being so bad.

So, a professor in Alabama goes in search of the beast in the Okaloosa mountains. The budget for the movie must’ve been a matter of pocket change. Anyway, the beast has been “killing” anyone who ventures into the mountains and the professor wants to prove it exists. He’s backed by a guy with money, who isn’t explained at all, and his university office is less well equipped than an average undergrad’s dorm room. He takes a female grad student with him but his financier, unbeknownst to the benighted professor, hires a bunch of beefy guys with assault rifles to go along, although they’re only going to take pictures. Of course the professor sleeps with the grad student but then the head of the tough guys kidnaps her as the beast kills off the tough guys’ heavily armed posse. Turns out the local hillbillies are, apparently, trying to mate the beast with the women who come into the woods. It’s worse than I’m describing it.

There is some chatter on the internet about this groaner, so I’m sure that I’m not the only one who’s seen it. Someone recently asked me how such movies even get made. Well, anyone with a camera can shoot a movie. Of course, getting paid screen time (or video distribution) is another story. I doubt the makers of this film made much money off of it, but since other suckers like myself have discussed it online, the producer, director, writer, and actor Richard Arledge, has the last laugh. His work is being talked about, no matter if nobody has a good thing to say about it. Of course, I wouldn’t have ever seen it at all, if I hadn’t had a hankering for Zontar: Thing from Venus all those years ago.