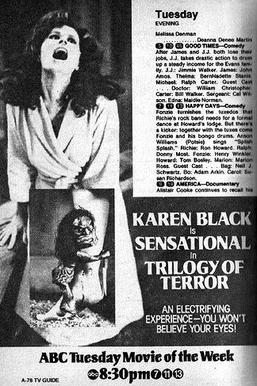

While reading about Dan Curtis, I became curious about Trilogy of Terror. As a child subject to nightmares, my “horror” watching was limited to Saturday afternoon movies on television and Dark Shadows (also a Dan Curtis production). In other words, I didn’t see Trilogy. While we were allowed to watch The Twilight Zone from time to time, I understand my mother’s reluctance to let us watch scary content. She was trying to raise three kids on her own, one of whom (yours truly) was plagued with bad dreams. Why would you let them watch scary stuff, particularly before bed? In any case, Trilogy was a made for television movie; Curtis did some theatrical films, but mostly stayed with television. It consists of three segments starring Karen Black, based on stories by Richard Matheson. Only the third one was scary.

The first two segments feature Black as either the apparent victim of blackmail or being controlled by a drug-addicted sister. The stories, being Matheson, have twist endings, but they don’t really scare. The final segment, for which the movie is remembered, involves the trope of the animated creepy doll. That made people sit up and pay attention. This wasn’t the first creepy doll exploited by horror, but it did predate Child’s Play and, of course, all those Annabelle movies. The doll here was a Zuni fetish. Its purpose is to enhance hunting skills and, of course, it comes with a warning. Don’t take off its golden belt or the spirit trapped inside will be released. The belt comes off, of course. The doll naturally attacks Black and, not being really alive, can’t be killed. The movie made an impression back in the day and is difficult to locate now without shelling out a lot for a Blu-ray disc. (Diligent searching will lead to streaming options, however; trust me.)

Having inherited more realistic scary dolls in the franchises mentioned above, it takes a bit of imagination to realize how frightening this would’ve been in the mid-seventies. Although a Zuni fetish isn’t a toy, killer toys had appeared before and would appear again. They all seem to rely on the uncanny valley where things resemble people but we know they’re actually not. We survive by being able to read other people and getting an idea of their intentions. The fetish here has pretty clear violent intensions, being a hunter with pointy teeth. We all know that there are some people like that. Such television movies aren’t always easily found, and if they’ve become cult classics like Trilogy of Terror, discs are priced pretty outrageously. If you’re unrelenting in your searching, you might just find your possessed doll. And an early example of what’s still a pretty scary idea.