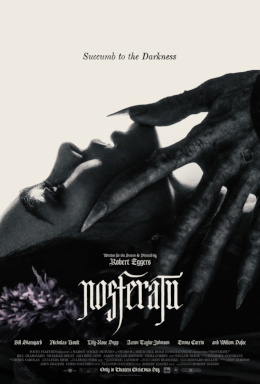

I had intended to see it in the theater, but holidays are family time. And not everyone is a fan of horror. Last night I finally did get to see Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu. Eggers is a director I’ve been following from the beginning. Here’s a guy who pays very close attention to historical detail. No slips in letting modern language expressions creep in. Costume and setting designs immaculate—nothing incongruous here. I was surprised that he was taking an established tale that’s based on a technically illegal film from Bram Stoker’s Dracula as his starting point. Still, I’m looking forward to Werwulf, probably about two years from now. (And speaking personally, I’d love to see his take on Rasputin.) In any case, Nosferatu. I avoided trailers and online discussions because I wanted to come to it fresh. He’s managed to make a disturbing story even more disturbing.

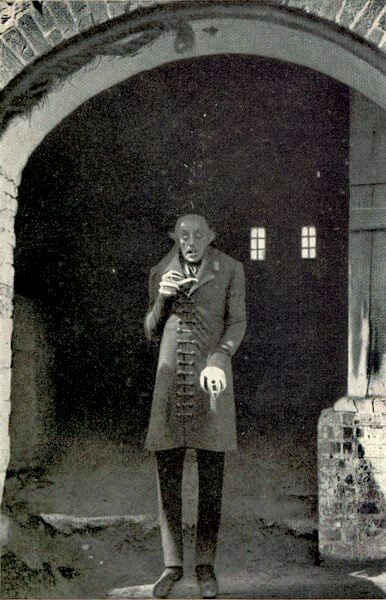

If you’re reading this you probably know the basic story. F. W. Murnau’s 1922 Nosferatu was in violation of copyright of Dracula, and so the basic story is similar. Eggers manages to bring to the fore the vampire as sexual predator angle. He prefers to bite chests and take long, slurping drinks. I said it was disturbing. And Orlok really looks the translation of the title, “undead.” Even at over two hours Eggers has difficulty fitting in all the elements of the story. And there are some unexpected aspects thrown in as well. In my mind, I couldn’t help compare it to Werner Herzog’s remake. Both are art-house treatments of Murnau’s work, which was itself German expressionism. All three are memorable in their own way.

The one character I didn’t fully buy was Willem Dafoe’s von Franz (the van Helsing character). This often seems a difficult one to cast. In Bram Stoker’s Dracula Anthony Hopkins just doesn’t do it for me either. It must be difficult to pull off eccentric but deadly serious. The unsmiling obsessive. That, to me, would be even more disturbing. Ellen Hutter’s fits are amazingly done and there’s a menace to her melancholy that really works. I’ve never seen Lily-Rose Depp in a film before, but she seems poised to become a believable scream queen. I was exhausted after watching the movie after a long day at work (there’s a reason to see things in a theater over the holidays, I guess), but after a night of strange dreams, I awoke to find myself wanting to watch it again. That’s the way Eggers has with films. They reward multiple viewings. And although this story’s familiar from the many versions of Dracula out there, it emphasizes some elements that have, up until now, often only lurked in the shadows.