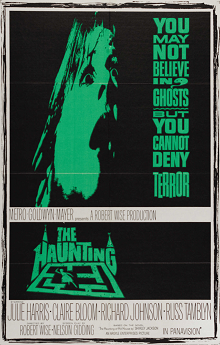

It’s funny what a difference that a few years can make. I can’t seem to recall from where I sourced my movies in the noughties. Streaming was extremely tenuous in our Somerville apartment—the plan didn’t include the required speed for it. Like in the old days when it took twenty minutes to upload a photograph through dial-up. In any case, I know I’ve watched The Haunting before. I know it was in Somerville, but having watched it again I have to wonder if my mind is playing tricks on me. I read Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House there, and I saw the movie. But how? It’s all about mind games, but the mind games are played on a woman who has an abusive family, one that damages her psychologically. Escape is important to her, even if it is to a haunted house.

I think the last time I watched this I was looking for something that might scare me. That phase was one of thinking not much frightened me—but this movie is scary. Even with its “G” rating, its lack of blood and gore, and black-and-white filming. It scares. One thing I’ve noticed when reading about these older movies after I watch them is that many improve with time. Shirley Jackson was known during her life but you become a classic writer only AD—after death. The Haunting has aged well. I suspect it has something to do with Robert Wise, the director. What must the psychology of a man be who directed The Sound of Music, The Day the Earth Stood Still, and The Haunting? The latter is all about psychology.

Movies that make you think are those, I believe, that may become classics. And perhaps there’s a bit of Eleanor inside all of us. Wanting to be noticed but eschewing publicity. Needing someone to love us, but pushing away those who try. Children in bad environments learn unorthodox, and often unhealthy, coping techniques. Eleanor has difficulty accepting that John is married when she thinks she’s finally found a place that accepts her for who she is. Even if it’s a haunted house. Especially if it’s a haunted house. As a child I’d no doubt have found the movie boring. There is, however, much for adults to absorb. And, I expect, I’ll need to go back and read the novel again. One of the reasons for watching horror is that the viewer is seeking something. It’s not just thrills. I didn’t write about the movie the last time I saw it so I don’t recollect when it was. Or even how. My thoughts now, however, are that I should’ve paid closer attention the first time.