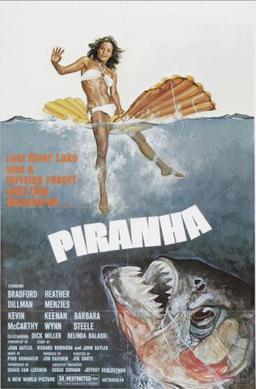

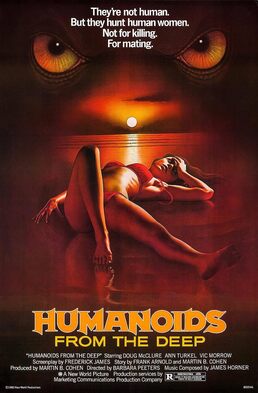

With a career as prolific as Roger Corman’s was, it’s difficult to keep up. I knew his horror movies mostly from the sixties and maybe early seventies. Having stumbled upon Humanoids from the Deep, which he produced rather than directed, I was pointed to Piranha. I knew about this movie, of course, but never had a reason to watch it. Well, Corman rabbit holes are easy to tumble down. Corman was the executive producer of Piranha and since I was already splashed with water-themed horror, well, why not? As with Humanoids, it has a different feel from movies Corman directed, but some of the trademarks are there. Piranha has so many shark-sized holes in it it’s not difficult to believe that it was exploiting the popularity of Jaws. In fact, the movie opens with one of the characters playing a Jaws video game.

So the government had been weaponizing piranhas to help in Vietnam but when the war ended they kept the program going. A woman who finds missing persons releases these fish into a Texas mountain stream. Anyone on the river is in danger and, of course, it flows past a new resort that is having its opening weekend downstream. The government wants a coverup because the colonel in charge has invested heavily in the new resort. You get the picture. Lots of people screaming in the water and a gratuitous use of movie blood and a story that keeps the viewer asking “why?” The film has a way of somehow steering just clear of bad movie territory. Also, it becomes obvious, that even without appropriate music cues, this is a horror comedy. I lost track of how many unanswered questions there were within the first fifteen minutes.

Piranha is a sort of fun knockoff from Jaws. There’s nothing really profound here, although one scene did make way for a little social commentary. When Maggie (the skiptracer) wants to distract an army guard with her feminine wiles, she wonders if he might be gay. This was in 1978, well before “don’t ask, don’t tell,” and she asks with a pre-Trumpian nonchalance that it’s downright refreshing. Otherwise it’s pretty much your typical exploitation film. The concept has led to a couple of remakes, so watching swimmers getting nibbled to death obviously has some appeal. The plot is so outlandish that there’s nothing scary here, even though it’s clearly horror. There’s even a scene with some stop-motion animation of a creature in a subplot that’s simply dropped. There are worse movies for summer escapism, given that we’re now post-pre-Trump again.