Last year, when The Conjuring was released, it quickly became one of the (if not the) top earning horror films of all time at the box office. Based on a “true case” of Ed and Lorraine Warren—real life paranormal investigators—the film is a demonic possession movie that ties in the Warren’s most notorious case of a haunted (or possessed) doll, with a haunting of the Perron family of Rhode Island. (The Warrens were also known as the investigators behind the Lutz family in the case of the “Amityville Horror,” showing their pedigree in the field.) Given that Halloween has been in the air, I decided to give it a viewing. As with most horror movies, the events have to be dramatized in order to fit cinematographic expectations. Apparently the Warrens did believe the Perron house was possessed by a witch. In the film this became somewhat personal as the dialogue tied her in with Mary Eastey, who was hanged as a witch at Salem (and who was a great-great (and a few more greats) aunt of my wife). Bringing this cheap shot into the film immediately made the remainder of it seem like fiction of a baser sort.

Last year, when The Conjuring was released, it quickly became one of the (if not the) top earning horror films of all time at the box office. Based on a “true case” of Ed and Lorraine Warren—real life paranormal investigators—the film is a demonic possession movie that ties in the Warren’s most notorious case of a haunted (or possessed) doll, with a haunting of the Perron family of Rhode Island. (The Warrens were also known as the investigators behind the Lutz family in the case of the “Amityville Horror,” showing their pedigree in the field.) Given that Halloween has been in the air, I decided to give it a viewing. As with most horror movies, the events have to be dramatized in order to fit cinematographic expectations. Apparently the Warrens did believe the Perron house was possessed by a witch. In the film this became somewhat personal as the dialogue tied her in with Mary Eastey, who was hanged as a witch at Salem (and who was a great-great (and a few more greats) aunt of my wife). Bringing this cheap shot into the film immediately made the remainder of it seem like fiction of a baser sort.

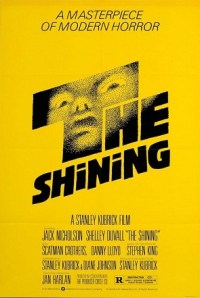

Witches may be standard Halloween fare, but when innocent women executed for the religious imagination are brought into it, justice demands separating fact from fiction. Writers of all sorts have toyed with the idea of real witches in Salem—it was a trope H. P. Lovecraft explored freely—but there is no pretense of misappropriation here. Lovecraft did not believe in witchcraft and made no attempt to present those tragically murdered as what the religious imagination made them out to be. The Conjuring could have done better here. It reminds me of Mr. Ullman having to drop the line about the Overlook Hotel being built on an Indian burial ground. Was that really necessary? (Well, Room 237 has those who suggest it is, in all fairness.) The actual past of oppressed peoples is scary enough without putting it behind horror entertainment.

A doctoral student in sociology interviewed me while I was at Boston University. She’d put an ad in the paper (there was no public internet those days) for students who watched horror movies. I was a bit surprised when I realized that I did. I had avoided the demonic ones, but I had been in the theatre the opening week of A Nightmare on Elm Street (on a date, no less) and things had grown from there. I recall my answer to her question of why I thought I did it: it is better to feel scared than to feel nothing at all. Thinking over the oppressed groups that have lived in fear, in reality, I have been reassessing that statement. What do you really know when you’re a student? As I’ve watched horror movies over the years, I have come to realize that the fantasy world they represent is an escape from a reality which, if viewed directly, may be far more scary than conjured ghosts.