When January starts grinding you down you have to find something to hang onto. See, I even ended a sentence with a preposition. January. If I’m not careful I can find myself getting quite depressed, so a bit of self-induced music therapy helps. Although I hate to admit it, I am a bit of a fussy person when it comes to my likes. My music tastes are quite personal and I mourn when a performer I like retires or dies. There’s not a ton of stuff that I enjoy and I don’t listen to music as often as I should. I work from home most days so I could have music on, but I find it hard to read (which is much of my job) with music playing. Like I said, fussy.

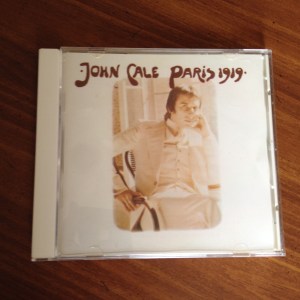

The other day—a weekend—I pulled out John Cale’s Paris 1919. John Cale is an underrated member of the Velvet Underground. Okay, with Lou Reed in the lead it’s gonna be tough to stand out. Cale, who suffers from competing with J. J. Cale (who was actually John Cale too; I empathize!), is a very thoughtful lyricist. Despite having been abused by a priest in his youth, he sprinkles his songs with religious references. “Andalucia” is a haunting single with the words “castles and Christians” hanging there for anyone to interpret. And “Hanky Panky Nohow” has an intriguing line about nothing being more frightening than religion at one’s door. There’s something profound here.

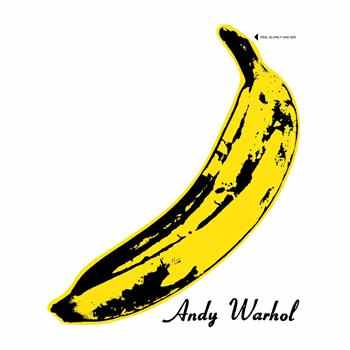

I grew up listening to The Velvet Underground & Nico when my older brother played it and the curtain door between our rooms didn’t block any sound. The only performer I could name was Reed. Years later, when the music of my young, virginal ears started in with a longing I couldn’t explain, I bought the album and learned of John Cale. I have to confess that I first encountered his name as the performer of Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” in Shrek. It drove me nuts when ill-informed students used to say it was Rufus Wainwright; yes, he performed it on the CD, but not in the movie. John Cale is one of those somewhat offbeat singers, who, like Nick Cave, salts his songs with images of a Christian upbringing that show a grown man clinging to something to which he somehow can’t fully commit. It makes us who we are and then leaves us wondering. It must be January.