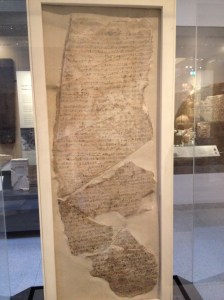

As a bibliophile it’s kind of embarrassing to admit that I’ve only just learned about the world’s largest book. If you’re like me you’re probably imagining an enormous tome that required acres of trees and fifty-five-gallon drums of ink to print. But that’s not it at all. This particular book is located in Mandalay in Myanmar. If I say it’s a religious text you might be clued in that it represents the Tripitaka, or Pali Canon. These are Buddhist scriptures. They are extensive, as scriptures tend to be. I’m certainly no expert on religions in that part of the world, but it’s clear that the world’s largest book, as a monument, required a massive amount of effort to put together. Housed at the Kuthodaw Pagoda, the texts were inscribed on stone housed in 729 stupas that are stunningly beautiful. (Take a look for other photos online—it’s impressive!)

The monument was completed in 1868. When the British invaded southern Asia, however, there was much looting and damage was inflicted on the shrine. It was eventually repaired and still stands as the largest book in the world. It’s no real surprise that this honor would be relegated to a religious text. Bibles of all sorts become symbols and their symbolic nature often supersedes what’s written inside. The idea of the sacred book has an unyielding grip on the human psyche, whether we think the book comes from God or an enlightened human being. Indeed, the sacred itself is an integral part of being human. When one group wants to dominate another, it often goes for its sacred artifacts. Cathedrals as bombing targets in the Second World War demonstrate that well enough. Ironically, we’ve ceased paying much attention to the sacred but we still revere it.

Books represent the best of our civilizing nature. They’re ways of coming to see the point of view of others. It really is a privilege to read. Banning books is, in its own form, a crime against humanity. Those who ban almost inevitably end up promoting yet more sales of the offending book. I often see books that make me angry or upset. My knee-jerk reaction is to want to deface them—this is a human enough response. But taking time to reflect, I realize that these writers are entitled to their opinions, benighted though they may be. A civil exchange of ideas is essential to getting along in a world with billions of different opinions. Every nation should have a monument that shows its love for books.