Halloween is the favorite holiday of many. I suspect the reasons differ widely. Although the church played a role in the development of this celebration, it didn’t dictate what it was to be about. It was the day before All Saints Day, which had been moved to November 1 to counter Celtic celebrations of Samhain. Samhain, as far as we can tell, wasn’t a day to be scared. It commemorated and placated the dead, but it wasn’t, as it is today, a time for horror movies and the joy of being someone else for a day or a few hours. There isn’t a preachiness to it. Halloween is a shapeshifter, and people love it for what it can become. If December is the month for spending money you haven’t got, October is the month for spooky things. Halloween is the unofficial kick-off of the holiday season.

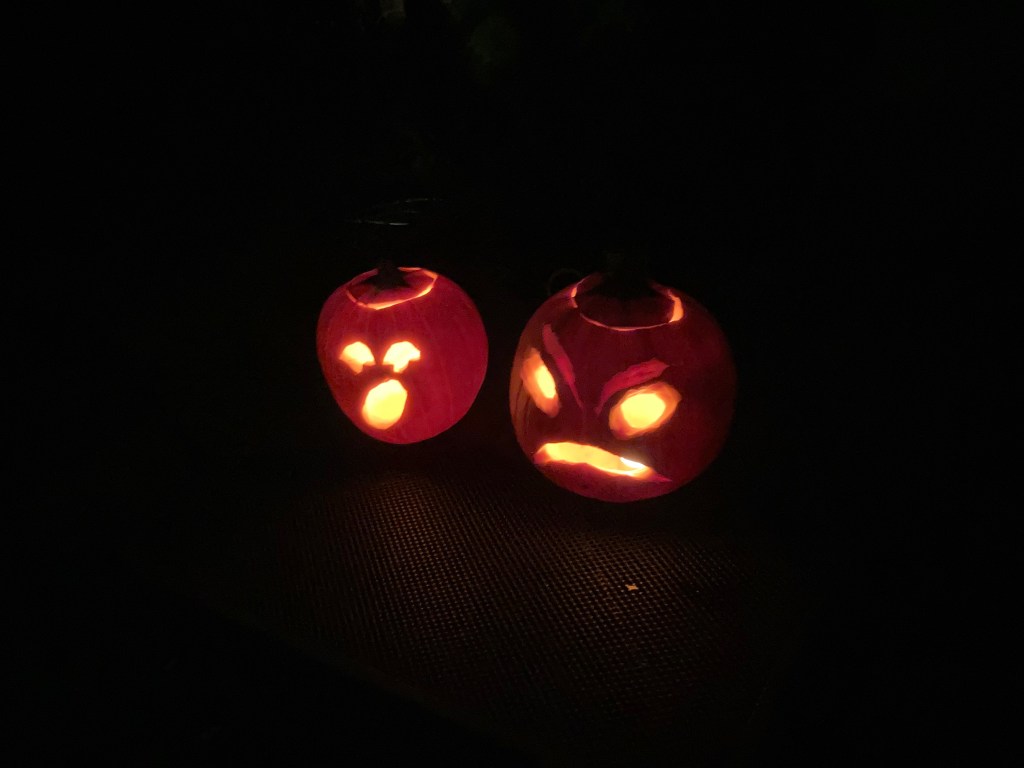

For me, it’s a day associated with dress-up and pumpkins. Both of these bring back powerful childhood memories. The wonderful aroma of cutting into a ripe pumpkin can take me back to happier times. I remember dressing up for Halloween as far back as kindergarten. I could be someone else. Someone better. It was a day when transformation was possible. I’m probably not alone in feeling this, although I’m fairly sure that wasn’t what was behind the early use of disguises this time of year. I’ve read many histories of Halloween and they have in common the fact that nobody has much certainty about the early days of its inception, so it can be different things for different people. Even within my lifetime is has moved the needle from spooky to scary, the season of horror movies and very real fear.

There’s a strange comfort in all of this. A knowledge that if we can make it through tonight tomorrow will be somehow less of an occasion to be afraid. It is a cathartic buildup of terror, followed by the release of being the final girl, scarred, but surviving. And people, from childhood on, enjoy controlled scares. Childhood games from peek-a-boo to hide-and-seek involve small doses of fear followed by relief. The future of the holiday will be open to further interpretation as well. As a widespread celebration it is still pretty young. And like the young it tests its limits and tries new things. At this point in history it’s settled into the season of frights and fears in the knowledge that it’s all a game. I wonder, however, if there isn’t some deeper truth if we could just see behind its mask.