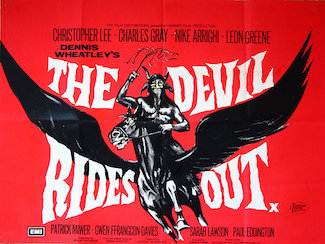

Many movies appreciate in value over time. The Devil Rides Out (also known as The Devil’s Bride) was not well received initially, but has become a highly regarded horror classic. One of the few with a G rating, no less. It’s also hard to see in the US, due to lack of streaming (at least where I stream) and DVDs coded to Europeans viewers. Anyway, taken from a Dennis Wheatley novel, and screen-written by Richard Matheson, it features Christopher Lee in an heroic role during the days just before public concern about Satanism would become downright panic. The story itself, effective if long-winded, develops among the aristocracy in England during the 1920s. It was released, by the way, the same year as Rosemary’s Baby, which helped play into the Satanic panic. Movies do influence the way we view “reality.”

I’ve never read any Dennis Wheatley novels, but it’s safe to say the story is pretty Manichaean in its outlook. A coven of Satanists wants a young man and woman to complete their number but the chosen young man has a couple of older friends who quickly comprehend what is happening and attempt to put an end to it. The Satanists, however, control real power and the movie is pretty much a tug of war between the young man’s friends and the coven. This is done in such a way that you see very little blood, no gore, and surprisingly for the subject matter, no nudity or sex. The Satanists here are old school—they want to worship the Devil in exchange for personal power. It’s pretty clear that some research was done before undertaking all of this, even if the paranoia born of such things was fueled by largely imaginary scenarios.

I’d been wanting to see this film for some time because of its clear connection between religion and horror. There’d be no Satan, as we know him, without Christianity. Indeed, there’s heavy Christian imagery in the film, in keeping with Wheatley’s outlook. Crosses cause demons to disappear in an exploding puff of smoke. Interestingly, however, there’s no crucifixes or holy water. This is a Protestant view of the Dark Lord. The Satanists, however, are defeated by the spirit of one of their own who refuses to allow them to sacrifice a young girl. The ending stretches credibility a bit more than the rest of the movie, but still, overall it isn’t bad. A Hammer production, it never had the box-office draw of its contemporary Rosemary. Still, The Devil Rides Out was influential in its own right. Even if finding a viewing copy requires almost selling one’s soul.