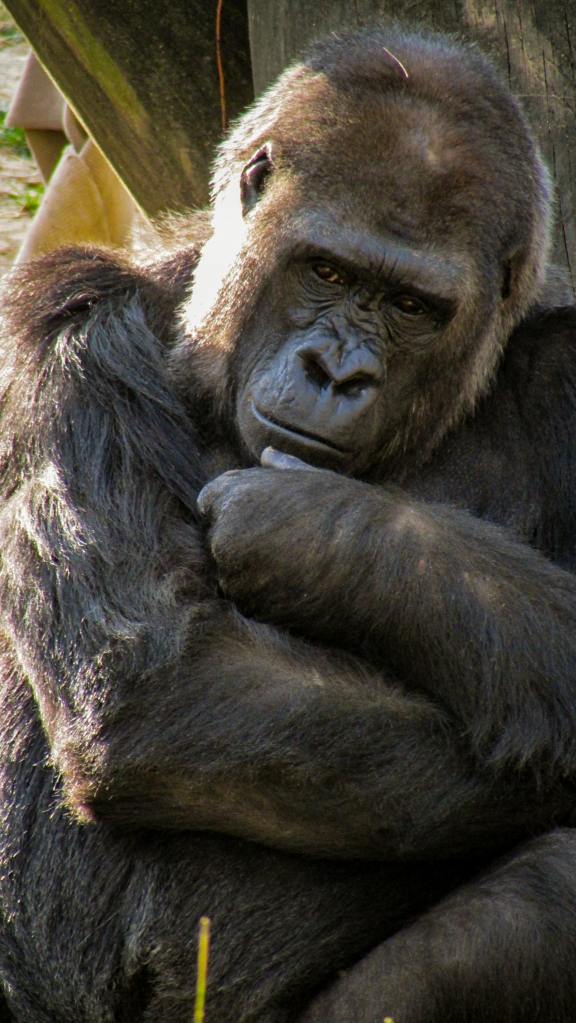

We don’t understand consciousness, but we want to keep it all to ourselves. That’s the human way. Or at least the biblically defined human way. Animals, however, delight in defying our expectations because they too share in consciousness. Take gorillas, for example. Or maybe start with cats and work our way up to gorillas. We all know that cats “meow.” Many of us don’t realize that this sound is generally reserved for getting human attention. Cats tend not to meow to get each others’ attention. According to Science Alert, gorillas in captivity have come up with a unique vocalization to get zookeepers’ attention. Not exactly a word, more like a sneeze-cough, this sound is used by gorillas at multiple zoos for getting human attention. Even if the gorillas have never met in person.

This is a pretty remarkable demonstration of consciousness. What’s more, it’s an example of shared consciousness. The same vocalization shared over hundreds of miles without a chance to tell each other about it. We’re very protective of consciousness. As a species we like to think that consciousness is uniquely human and that it’s limited to our brains. Moments of shared consciousness we chalk up to coincidence or laugh off as “ESP.” Funny things happen, however, when you start to keep track of how often such things occur. It might make more sense to attribute this to moments of shared consciousness. In our materialist paradigm, however, that’s not possible so we just shake our heads and claim it’s “one of those things.”

Animals share in consciousness. We don’t always know what their experience of it is—indeed, we have no way to test it—but it’s clear they think. I live in a town, so my experience of observing wild animals is limited to birds, squirrels, and rabbits, for the most part. I often see deer while jogging, and the occasional fox or coyote, but not long enough to watch them interact much. But interact they do. Constantly. These are not automatons going through the motions—they are thinking creatures who have sophisticated ways of communicating with each other. Ours includes vocalization, so far uniquely so in the form of spoken language. The great apes—chimpanzees and orangutans, according to Tessa Koumoundouros—also vocalize and do so with humans. Now we know that gorillas do too. And we all know that a barking dog is trying to tell us something. If we took consciousness seriously, and were willing to share it a bit more, we might learn a thing or two.