We develop pictures in our minds of the kinds of things that belong together in different eras. Dinosaurs, for example, don’t belong with our own species, no matter how much we may occasionally wish it were so. Horseless carriages don’t populate the seventeenth century and complex machines, we tend to think, didn’t really come about until medieval Europe (and then they were often used for torture). Our view of the world is, of course, one of comfort with the certainties of history. That’s why the Antikythera Mechanism is such a fascinating artifact. A very sophisticated device with gear trains and cranks and dials, it astonishes those who first encounter it in that it was made before the Common Era somewhere in the sway of ancient Greece. It is, in essence, a kind of computer. Long before Joseph met Mary.

We develop pictures in our minds of the kinds of things that belong together in different eras. Dinosaurs, for example, don’t belong with our own species, no matter how much we may occasionally wish it were so. Horseless carriages don’t populate the seventeenth century and complex machines, we tend to think, didn’t really come about until medieval Europe (and then they were often used for torture). Our view of the world is, of course, one of comfort with the certainties of history. That’s why the Antikythera Mechanism is such a fascinating artifact. A very sophisticated device with gear trains and cranks and dials, it astonishes those who first encounter it in that it was made before the Common Era somewhere in the sway of ancient Greece. It is, in essence, a kind of computer. Long before Joseph met Mary.

Alexander Jones’ A Portable Cosmos: Revealing the Antikythera Mechanism, Scientific Wonder of the Ancient World is a pretty thorough introduction to the device, including the mechanics of how it works as well as how astronomy works. You see, the Antikythera Mechanism was designed to demonstrate the relative motion of the planets, including the sun and moon. For a device in the geocentric world of ancient Greece, that’s pretty remarkable. It predicted eclipses and showed the phases of the moon. It also makes me ponder the fact that most ancient people considered the planets deities. Long before Newton, then, some were recognizing that even the gods could be made to work according to a crank and gears.

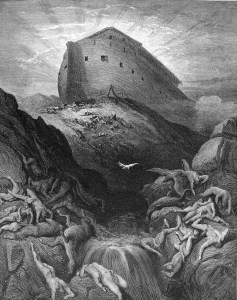

Science and religion coexisted peacefully in those days. Although only one such device has been discovered, it’s virtually certain that more existed. Gods and gears both had a place in such a world. Along the centuries, however, the idea grew that if gears worked, we no longer required a deity. Occam’s razor has its uses, to be sure, but it can shave a little too closely from time to time, nicking delicate flesh. The idea that one side only can be right—and since we can see with our eyes that science works—tends to favor the mechanistic universe. There’s no disputing that science makes our lives easier and that its method is self-correcting and generally effective. The hands that cranked that ancient geared device, however, likely belonged to a believer in gods. Such belief didn’t prevent progress, but then some kind of Fundamentalists killed Socrates for his own form of heresy. Perhaps the true answer lies in balance. It may also be the most difficult of principles, scientific or otherwise, to achieve.