The problem with lying is that it generally doesn’t hold up. Eventually people will figure out that a falsehood is exactly that and the liar will be scorned. In other words, truth is determined by witnesses. This is tested and confirmed every day in our legal system. The witness is invaluable (except in the hands of lawyers). Since no one person can see everything, we rely on others to help us fill in the blanks. Think of it; when you see something unusual don’t you ask whoever’s with you “did you see that?” We witness the world around us, and unless we’re untruthful that observation becomes part of the collective narrative of what the world is like.

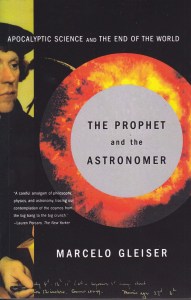

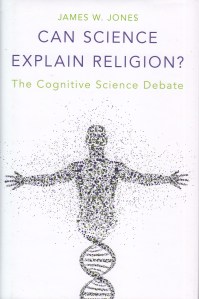

A story from IFL Science! sent by a friend describes “Ancient Legends And Myths That Were Later Proven True By Science.” Apparently this is part of an annual series. What the article lays out are recorded myths later confirmed by science. Scientists are trained witnesses. Taught to silo information, they separate belief (so they say) and eschew non-natural causation. They peer into the mirror each morning with Occam’s razor firmly in hand. Then everybody seems to be surprised when non-scientists have actually observed something correctly. This is the ancient bickering between religion and science—you can’t have it both ways, the reasoning goes. This is a zero-sum game. The winner takes it all. Reality, we observe, is seldom so simple. Articles like this one express surprise that non-scientists can get it right once in a while. The fact is, we’re all witnesses to what happens on this planet. Some of us are just taken more seriously than others.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m not equating religion and science. Nor am I suggesting that all people are equally good observers. It’s just that sometimes things happen when there’s no scientist in the room. Or if there is there’s no time to wire everything up appropriately. The events in the IFL Science! piece are all like this. Observed by people before science was invented—some of them before civilization was invented—events were called myths until scientists came round with their notebooks and validated the long-departed witnesses. The problem with occasional phenomena is that they don’t come on cue. The universe isn’t here to please us or satisfy our curiosity. It’s just that sometimes we see things that don’t match up with the textbook. Whether you call an exorcist or a scientist depends entirely on your point of view.