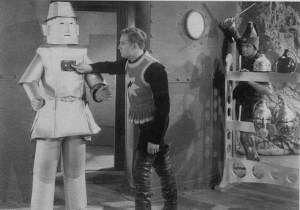

My snow day activities yesterday would not have been complete without the viewing of a classic science fiction film for relief from my Mythology course prep. Still having mythology on the brain, I selected Dr. Cyclops, a 1940s movie that presages many of the concerns evident in the more famous members of the genre over the next decade. There were, even before the atomic bomb, clear concerns with radioactivity and its control by unstable elements of society. The fact that Dr. Thorkel is stereotypically Germanic would certainly resonate with audiences of the day. Given the title I focused on the classical elements and they eventually came through. As the radioactivity shrunk the cast, with the exception of Dr. Cyclops (Thorkel), Odysseus’ plight in the cave of Polyphemus emerged clearly. The doctor is symbolically blinded by the hiding and breaking of his glasses, and the shrunken prisoners escape like Odysseus’ crew. In one scene where the rival Dr. Bullfinch (surely no accident) addresses the much larger Thorkel the writers make it clear for the viewers that Bullfinch is really Ulysses (Odysseus).

Presumably filmgoers in 1940 were still required to have read the classics in school so that such references would have been obvious from the start. Less obvious to viewers then and now is the fact that ancient mythology was a form of religion. Over the past week or so I’ve been participating in an exchange on Sabio Lantz’s blog, Triangulations, on the topic of metaphorical versus literal truth. I maintain that mythology reflects truth as perceived by ancient believers, whether they “believed” in an actual pantheon on Mount Olympus or not. Myths are intended to convey truth – although ancient religions were more often about correct practice rather than correct belief. Placating angry gods was the job of the priesthood, not the average citizen.

The question unanswered is when religion shifted from correct practice to correct belief. Correct belief can only truly apply in a monotheistic context – if there are many gods there are potentially many beliefs. With one god, one personality, the potential for believing incorrectly infiltrates a religion that is primarily concerned with keeping the many gods satisfied. So perhaps what Dr. Cyclops sees through his one good lens is a metaphor for seeking a single truth rather than the many. In the film, before he meets his demise in the radium mine, Dr. Thorkel is the only character with the stature of a god.