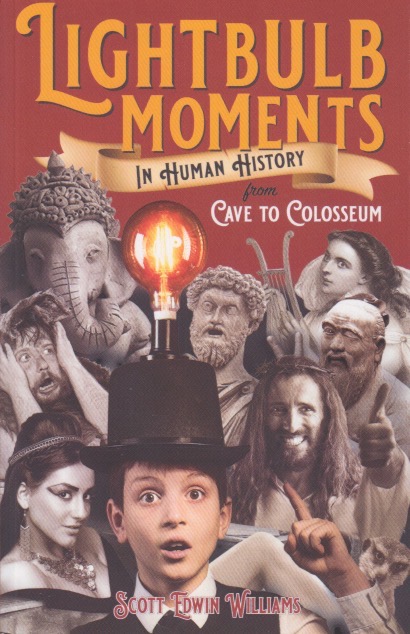

We could all use a little hope. Given the rate of change in the world it often feels impossible to catch your breath. And not only that, but the change often feels decidedly negative. Few would opine, for instance, that we live in the golden age of politics. And while it has its supporters, AI seems bent on our destruction. So why not eat, drink, and be merry? Scott Edwin Williams, whose last book Lightbulb Moments in Human History I reviewed here, has been at it again. His basic idea is that our “lightbulb moments” give us hope for a better future. Lightbulb Moments in Human History II: from Peasants to Periwigs, keeps the same general idea afloat, but barely. As history progresses it’s harder and harder to say that the lot of humanity, tout court, has improved. True, we live in relative comfort in “the developed world,” but we still have looming Trumps and other nightmares in the wings.

This book tries to cover large swaths of history, and that’s a difficult task. Williams tries to keep it lighthearted but even he struggles to do so when discussing the rise of big business. The chapter “Takin’ Care of Business” really showcases the negative traits that humans are too often willing to display when they form companies. Capitalism may have been a lightbulb moment, but the untold misery it has introduced into the world gives the reader pause. For example, the East India Company’s business decision to addict as many Chinese to opium as possible, seems quite strange in the context of a “war on drugs” being used as a means of incarcerating “undesirables” because, well, drugs are bad.

There are some signs of hope, and some lighthearted moments in the book. It does, at times, seem to work against its own thesis. It makes me glad for living in an age of anesthesia, and of general agreement that people should respect each other’s boundaries (unless you live next to Russia). Even the lightbulb moments of Mesoamerican/South American history demonstrate the kind of cruelty humans often perpetrate against “outsiders.” Williams notes here that two more books are in the works (authors know that a series isn’t a bad thing) but it does make me wonder if light and dark don’t balance each other out. I know from my own family history that some of my ancestors died of things quite curable today, and they lived not all that long ago. And that I can write these words and publish them instantaneously (whether or not anyone reads them). And I can buy most necessities of life (apart from toilet paper during a pandemic) fairly easily. And I do appreciate books that give me hope. But balance isn’t such a bad thing either.