On the DVDs of the complete The Twilight Zone (or at least the edition I bought over a decade ago), the opening sequence of seasons 3 and 4 both have a voice-over from episode “Five Characters in Search of an Exit,” calling out “Who are we?” In context, the disparate characters in a shapeless prison are, in reality, toys that have gained consciousness (and this well before Toy Story). Having gone through a traumatic scam, and trying to piece life back together, I spend a lot of time on the telephone trying to verify my identity. This isn’t a simple matter for a guy like me who constantly asks myself the question, “Who am I?” Descartes, going back to Aristotle, opined we enter life as a tabula rasa, a blank slate. Those of you who look around the other pages of this website will see that I have as a six-word biography “Missed the first day of school.” That must’ve been the day when they told us who we were.

Some people have a clear idea of who or what they are. The surround themselves with tchotchkes of their favorite animal, or symbol, or even screen idol. Or deity (deities). Others of us, it seems, are constantly searching, never quite satisfied that we’ve discovered our essence. I’ve mentioned before that during the CB craze of the eighties my handle was “Searcher.” I have an innate curiosity and I crave depth of knowledge. How do you symbolize that? How is it even an identity? I ask with Rod Serling’s characters, “Who are we?” I’m not sure who might answer that.

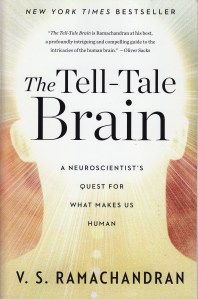

When I first started this blog I had some hope that I might once again become an academic researching ancient Semitic mythology. Working a 9-2-5 to acquire material for the company long ago meant that the full-time research needed to keep abreast of the field could not happen. For several years this blog consisted of wry interpretations of various political- or travel- or reading-related observations about life. As it became less focused on the world of the Bible I lost most of my original readers. I thought there might be potential in writing about my fascination with scary stuff. That caught my wife a bit off-guard since during the time we met, married, and began this journey together, that interest had been dormant. It revived when I lost the job that I thought defined me. I still write about horror but have recently felt the draw of dark academia. Meanwhile the representative from the bank is on the phone asking me to verify my identity. “It’s complicated,” I want to say.