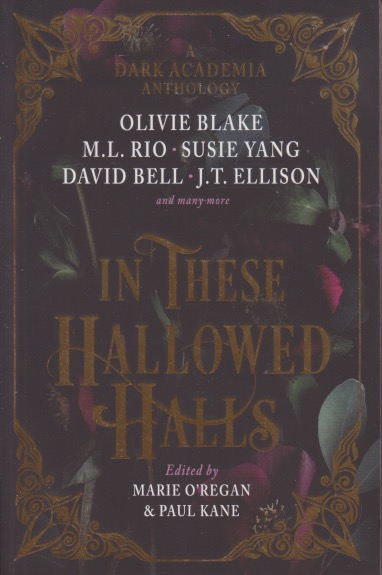

Every time I read a short story collection I tell myself I should do so more often. Knowing that you’re only committing yourself for maybe thirty or forty minutes at a time is one way to incorporate more reading into a life that’s incredibly busy. I read In These Hallowed Halls, edited by Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane, because, as its subtitle declares, it’s A Dark Academia Anthology. As with nonfiction anthologies, it is a mixed bag. The stories are all well written and all were enjoyable to read. They also display some of the breadth of dark academia. Most of the stories are literary (as a genre), others dip into science fiction and horror. Dark academia doesn’t specify whether a book (or story) will be speculative or not. As someone who writes short fiction, it seems that some of my tales might wag that way.

In any case, discussing a collection is tricky because there is such variety. Some of the stories stayed with me beyond reading the next, which could be quite different. Others I have to go back to remind myself what happened. These days it can take several weeks to finish a book and a lot can happen in real life in that time span. The stories that stay with me the most have obsessive narrators, or characters who are obsessed. This kind of story, I know from experience, is difficult to get published. Many of us who write, I suspect, do get obsessed. An idea latches on and won’t let go. Of course, most of us also have jobs that force the jaws open and drop us down in the world of the ordinary again.

Another thread that runs through many of these stories is how students struggle for money. That’s true to life. Thinking back to both college and seminary, there were times in both settings that I was working two part-time jobs as well as being a full-time student. And living like, well, a student. That experience, except for the truly privileged, is fairly common and our writers here recognize, and perhaps remember, that. The other unavoidable theme when writing about young people in college is, shall we say, hooking up. For many of us, college is that period in life when, thinking of our futures, and following our hormones, we start looking for love. (I know, high schoolers do that too, but college has a way of focusing your energies.) All of that swirling around the darkness that sometimes falls over our tender years makes this dark academia collection worth reading cover to cover.