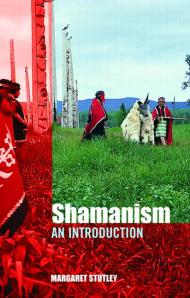

My reading habits are unorthodox. I don’t follow a fixed plan, but hope for something that will keep me engaged for the fifteen or so hours I spend commuting each week. I began October with a book about werewolves and followed it up with a book on the Hmong. Apropos of neither and both, I turned next to Shamanism: An Introduction, by Margaret Stutley. While not the best organized book, it does provide a smorgasbord of shamanistic traditions, principally from Siberia, where Shamanism was first recognized. Before I’d finished, I’d read about both epilepsy and werewolves.

My reading habits are unorthodox. I don’t follow a fixed plan, but hope for something that will keep me engaged for the fifteen or so hours I spend commuting each week. I began October with a book about werewolves and followed it up with a book on the Hmong. Apropos of neither and both, I turned next to Shamanism: An Introduction, by Margaret Stutley. While not the best organized book, it does provide a smorgasbord of shamanistic traditions, principally from Siberia, where Shamanism was first recognized. Before I’d finished, I’d read about both epilepsy and werewolves.

Shamanism is not a “religion” per se. There is little agreement among scholars about what a religion is at all. Shamanism is very much a local set of beliefs and practices that have only very basic elements in common (shamans being one of them). It is a good example, however, of how moral heathens can be. Shamans often accompany egalitarian societies who do not require governments and religious leaders telling them to be nice to each other. No, this is not the noble savage myth, but it is a clear indication that major religions are not required for morality. It evolves on its own. Often shamanism is not constrained by overly left-brain influence, and sees connections science can only deny. The plight of Lia Lee was explained here in a way physicians could access—epilepsy and other diseases are problems of the soul as much as the body—if only they read books about religion. Healing involves calling the soul back. Treatment of the body misses the point. And sometimes the dead become werewolves.

We live in a world where real suffering is caused by lack of understanding about religion. Assuming a cultural hegemony of Christianity, or Islam, and sometimes even other religions, we discount those who believe differently than we do. The New Atheists frequently overlook just how seriously people take the world of the emotions and belief. That realm is a large part of what makes us human and it plays by no logical rules. Nor does it care to. In a country, such as the United States, where money is believed to be the very warp and woof of the good life, shamans sometimes secretly cut the thread. Still, don’t ask universities to expand the study of something as insignificant as religion because all intelligent people know that nobody really believes that stuff any more.