Early film research owes great debt to YouTube. Many historic and significant films cannot be purchased or watched anywhere else. Even in this uber-greedy late capitalist era, few (if any) are willing to sell that for which many would pay. This is brought on by my learning about Alice Ida Antoinette Guy-Blaché, also known as Alice Guy. Guy was the first female film director. She left a substantial body of work and is credited with being the maker of the first narrative-based film in history. If you’ve not heard of her, you’re not alone. Even during her lifetime she wondered why she was never recognized for her cinematographic achievements, incredible though they were. She filmed one of the first adaptations of an Edgar Allan Poe story known, The Pit and the Pendulum (1913). This one is partially lost—many early films are.

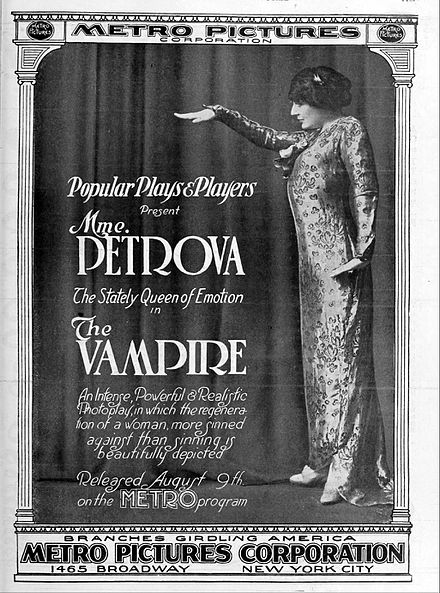

I wanted to see her 1915 film, The Vampire. Given the date, you will have correctly guessed that it’s a silent movie. It still survives and the only place it can apparently be found is on YouTube. Before you run off and watch it, be aware that it’s not about a literal vampire, but rather “a woman of the vampire type.” The current term is “vamp.” The movie, which takes a feminist approach, is framed around Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “The Vampire.” It runs for about an hour, which was pushing the envelope in those early days of cinema. It tells the story of a happy, wealthy family broken apart by a “vamp.” The husband receives a government appointment in Europe and his wife and daughter can’t follow for a month. On the way over by ship, the vampire seduces him, after compelling her current love to shoot himself. This isn’t a comedy.

The film doesn’t end happily—the statesman, aging prematurely, just can’t break the vampire’s hold on him. Still, friends and family urge his wife to wait for him because divorce is wrong. The film lingers on the suffering of the wife and on how much his young daughter misses her father. The film quality is quite good for the time, although the YouTube version has been digitally restored. So this isn’t a horror film, but watching it is a tribute to a woman who influenced filmmaking and then was summarily forgotten, largely because of her gender. Alice Guy was the first woman to run her own movie studio. Sadly, her husband left her and their children just three years after The Vampire. Shortly after that Guy’s filmmaking career was over. Fortunately for history, Guy has been rediscovered and has been receiving credit for her pioneering work. Although The Vampire was about a dangerous woman, the reality is, and was, that patriarchy continues to ruin women’s lives.