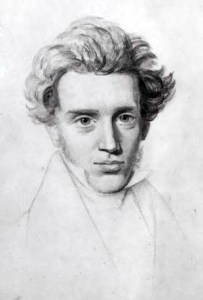

“Time,” Morpheus said, “is always against us.” Such is life in the Matrix. Wake before daylight. Climb on a bus. Stare at a screen for a solid eight hours. Climb on a bus. Sleep before dark. Repeat. It’s a schedule only a machine could appreciate. Since I was a seminary student, I’ve considered time an ethical issue. Take waiting in line, for example. This is difficult to convert to a good use of resources. In circumstances where the queue is anticipated, such as waiting for a bus, one might bring along a book. The unexpected line, however, is wasted time. Paying Agent Smith his due. This all comes to mind because of a recent news blurb about Søren Kierkegaard. The story in Quartz, cites the Kierkegaard quote: “Of all ridiculous things the most ridiculous seems to me to be busy—to be a man who is brisk about his food and his work… What, I wonder, do these busy folks get done?”

I’m a lapsed Kierkegaard reader. The sad fact is that philosophy takes time. You can’t sit down and whiz through it. You need to stop frequently and ponder. This was the life of the academic that I once knew. Before the Hindenburg. Before capitalism became my raison d’être. You see, you can never give too much time to work. There’s always email. The internet has wired us to that which once wired money. “We are the Borg.” There’s no time for a Danish and a concluding unscientific postscript any more. We willingly comply because the rent is due. What, o Søren am I getting done?

We rush around, it seems to me, because when labor-saving devices were invented they only led to more labor. Our European colleagues look with wonder at our febrile, frenetic pace. They wonder where it has gotten us. Has the final trump indeed sounded? Has the stock market become divine? Has money become the only Ding an sich? Kierkegaard wears a thick layer of dust on my shelf. Once I spent an entire day trying to digest a single paragraph of his writing. Now I brush him off like crumbs from my danish and I don’t have time to finish my coffee since the till is calling. I will get back to you, Søren, truly I will. It’s just that I have this never-ending task to accomplish first. After that we’ll sit down and have a leisurely talk.