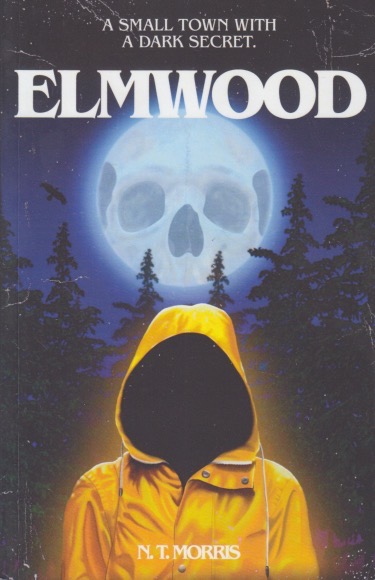

Publishers use the term “deep backlist” to refer to titles that they published long ago. That’s always the phrase that comes to mind when I browse my “to read” list. That list was started, in its current online repository, a decade-and-a-half ago. When I delve into the “deep backlist” of items I placed on the list years ago I sometimes can’t remember where I learned about them. Such was the case with N. T. Morris’ debut novel, Elmwood. Someone recommended it years ago and I finally came into possession of it. A moody tale about a town haunted by a cult, it is a nice effort as a self-published horror novel. If you read a lot of fiction you start to notice some of the signs with self-published work (and there are many good reasons to go that route). Morris offers a well-designed and aesthetically pleasing book. The story does end with some loose threads, however. There may be spoilers below.

Aidan Crain finds the victim of what appears to be a serial killer. His difficulty coping with it leads his wife Laura to suggest that they get away from it all in the little town of Elmwood. They rent out a house she found online, but it turns out to be haunted. The people of Elmwood aren’t terribly friendly to strangers, but since the goal is to get away from city life, the young couple doesn’t much mind. Except the ghosts in the house are accompanied by a dark presence in the woods that keeps calling to Aidan. One of the tricky bits for me was determining what were dream scenes and how they related to waking scenes. This is often part of speculative fiction, but a solid editor would lead you in the right direction in such situations.

The story tries to fit a lot in, leading me to think—rather uncharacteristically—that it needs to be longer. The house was owned by a serial killer who’s part of the cult that killed the victim Aidan found many miles away. The cult has been culling both locals and visitors for years and the police department appears to be complicit. As do some local business owners. The darkness in the woods, which is defined more or less as evil itself, seems to control the cult and it wants Aidan to join. Some of the loose threads at the end suggest that Morris’ next novel will be a sequel to this one. I can’t recall how I learned about Elmwood, but I’m glad to have finally read it. It’s a good shot at becoming a horror writer from my personal deep backlist.