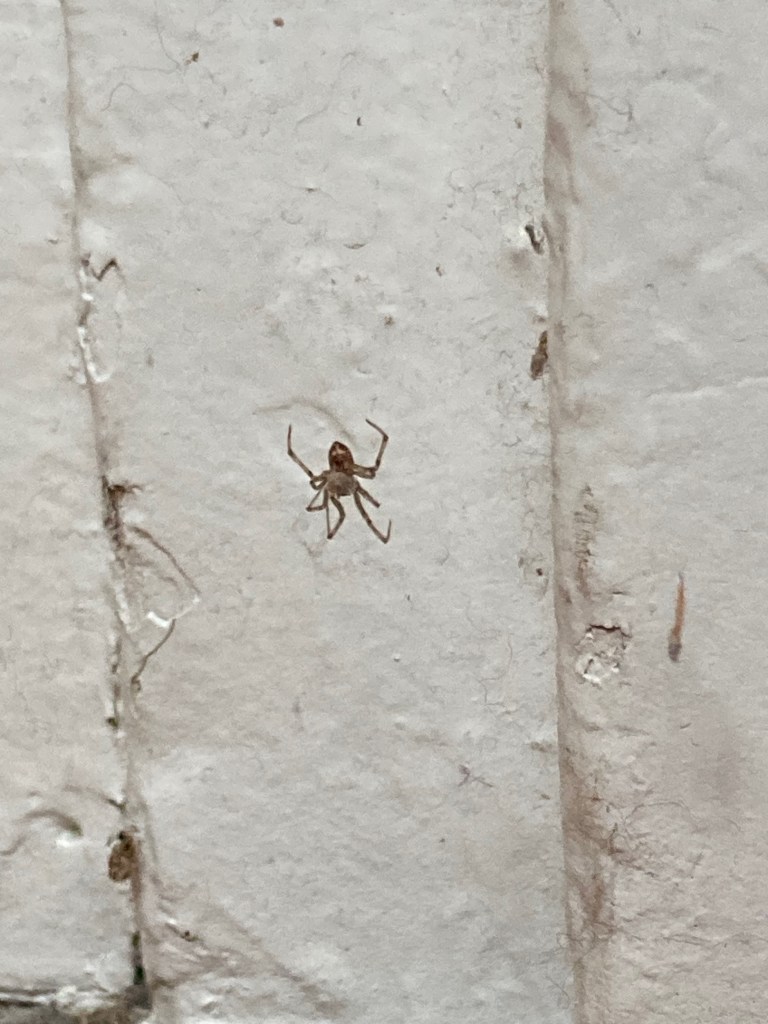

I give them names, the spiders who choose to live in our house. That’s how I named Henry, shown in the photo. I grew up with an almost debilitating arachnophobia, and as with most of my fears, worked hard to overcome it. So when a spider moves in, I let them stay. Unless they’re too big. Here’s where it becomes interesting. Like quantum mechanics, there seems to be an arbitrary point when something is “too big” for the rules to apply. What is that tipping point? The other day I bumbled into the kitchen early to get some water, having given up coffee years ago. There was a spider that I could see from across the room. It was very large. It’s a sign of how much I’ve overcome my phobia that I was able to walk around the counter and to the sink to fill up. I kept a wary eye across the room, however, in case Octavian made any funny moves.

The spider held very still, as arachnids often do when they know they’ve been spotted. I sometimes wonder if they know how scary they are to other creatures. I searched around for a jar large enough to catch and release, without pinching any legs, and crept over. Turns out Octavian was faster than I am first thing in the morning. And, honestly, I was still recovering from a vaccine that had knocked me out the day before. At least I can blame that. I wonder if that’s one of the reasons fear of spiders is so widespread—they’re fast. Or is it something inherently menacing about those eight legs? I’ve never experienced any kind of octopus phobia, so I can’t think that it’s merely the number. The jointed legs? That seem disproportionate to the body size? Whatever it is, days later I’m still cautious in the kitchen.

I have a great appreciation for spiders. I don’t like to be startled by them, but otherwise, if they keep their distance, I’m fine with them. I do wonder what they think, living in a world of giants. Some insects, in the same size range as arachnids, seem ignorant of the human threat. It’s not unusual for an ant to find its way inside and walk right up your foot and leg, oblivious to the danger. They seem to have no fear. Spiders, however, do. They’re very good at running and hiding. I like to think they know our house is generally a safe space, until the vacuum cleaner comes out. When I’m behind it, I always try to give Henry and his friends a chance to get out of the way.