I remember seeing a television commercial once (not during the Super Bowl) where an older guy, a lawyer, complained at the camera, “It used to be that lawyers didn’t advertise.” He went on to say that he felt uncomfortable promoting himself since it was in poor taste, but since the legal profession had swung that way he was entering the game. I know how that guy felt. I grew up with the firm notion that self-promotion was in bad taste. If my career has taught me anything, it’s that unless you’re born well connected, if you don’t promote yourself nobody else will. Still, it rankles. With that hearty introduction, I would, in poor taste, point out that my latest article has been published. Those of you who keep an eye on this blog will know that I gave a paper about the Bible in Sleepy Hollow to a learned society a couple years back. That paper is now available in the Journal of Religion and Popular Culture.

Doing research is difficult when you don’t have institutional support to carry it out, but doing such things as an independent scholar can be kind of liberating. I used to research, write, and get published an article a year, back in my teaching days. Nashotah House didn’t have the greatest library, but they did have interlibrary loan and, towards the end of my time there, internet access. More than that, life wasn’t measured in increments of nine-to-five. Living on campus, commuting could be measured in seconds rather than hours. Although publication didn’t bear the weight there that often pressures academics elsewhere, like that lawyer whose name I can’t remember, I wanted to be in the game. I guess I still do.

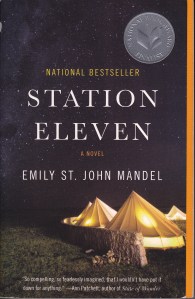

In these days of uneducated government, if you don’t do it yourself nobody’s going to do it for you. It’s what I once called “the educational imperative.” We are duty-bound, as conscious beings, to move knowledge forward. How many apocalyptic scenarios are there where, when the powers that be devolve into inanity, the monks in their cloisters have to keep knowledge alive? (The question’s rhetorical.) I’m reminded of Station Eleven by Emily St. John Mandel since there women do a good bit of keeping the culture alive when society collapses. Or, to put it another way, like Sleepy Hollow. When the forces of evil break into the world, it’s an African American woman who saves it. If your school has access to JSTOR, you’ll be able to find out more in my paper.