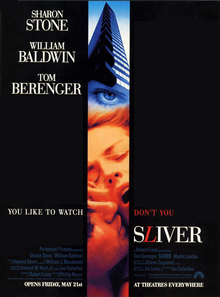

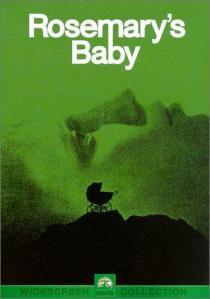

I saw that it was based on a novel by Ira Levin, and it was free on Amazon Prime, so I watched it. I’m not sure Sliver did much for me, however. Ironically I watched it a weekend after watching another Sharon Stone movie that had been panned, Diabolique. (Stone grew up not far from me I learned, but then, it’s a small world.) Something I’ve noticed about myself is that my limited experience sometimes sets false expectations. My experience with Ira Levin has been The Stepford Wives and Rosemary’s Baby. I read both novels and saw both movies. I’d classify them as horror, so I guess I thought that’s how Ira Levin translated to me. What Sliver (the movie) suggests to me is that Levin must’ve been really conflicted about living in New York City. In both this movie and Rosemary, getting a great apartment always comes with a hidden problem of a major kind.

Sliver is a bit difficult to figure out because the original ending was changed so I’m not sure what to believe. One thing I know for sure is that movies that make a character work in publishing are never shot by someone who actually does work in the industry. Either that or I’ve been shortchanged. In the movie Carly Norris (Stone), who moves into the Sliver, has a huge office. I’ve only ever had cubicles, if even that. No oak paneling and book-lined walls for me. In any case, the movie focuses on Carly’s home life because two men fall for her as soon as she moves in. One of them is a killer (this was what was changed with the rewritten ending), and both of them are creeps. One spies on everyone in the building through hidden cameras and microphones, and the other has affairs with the young, single women. And maybe kills them.

I guess I was expecting something more like the original Stepford (the remake—why?) or Rosemary. Both had a message with plenty of social commentary, it seemed to me. Of course, both of them were pretty close to the book. (I’ve not read this novel. Perhaps I should.) Sliver, at least the film, was more a matter of moving into a building with a mystery and not knowing whom to trust. It really didn’t suggest much about surveillance, or women’s agency or lack thereof. It did make a case for not moving to New York City. I don’t know how an editor could possibly afford such a nice apartment, in any case.