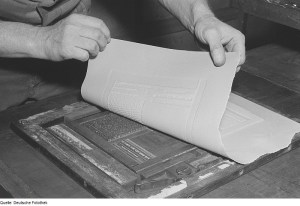

In the early days of publishing, type was set by hand. Individual letters, inserted backward onto plates, were used for printing the positive of a page. Printers could make as many pages as desired, but once the letters were released, it was time-consuming and costly to arrange them all again. If a book (principally) was expected to sell well enough for reprints, a plaster or papier-mâché mold was made of the page. This could be used to cast a solid metal plate of the pages to store for future print runs. This solid plate was known as a stereotype. Every copy from the plate would be exactly the same. When the plate was no longer needed it could be melted down and recast. The origin of stereotyping is a useful reminder of what happens when we preconceive a notion. For example, if I write “computer programmer” there is probably an image that comes to mind. No matter how many stereotypes confirm that mental picture, it isn’t true to the original.

A piece by Josh O’Connor on Timeline, “Women pioneered computer programming. Then men took their industry over,” tells the story. Back in the early days of computing, when programming was seen as the menial labor of swapping out cables and plugs, it was “women’s work.” When it became clear how complex this was, and how many men didn’t understand it, the job was upgraded to “men’s work” and women in the industry were replaced. Stereotyping wasn’t just for boilerplate any more. The unequal assumptions here have led to a situation where computer engineering jobs still overwhelmingly go to men while women take on more “gender appropriate” employment. Any task that requires mental calculus benefits from input from both genders. One’s reproductive equipment is hardly a measure of what a mind is capable of doing.

Stereotyping is so easy that only with effort can we force ourselves to stop and reevaluate. The computer industry is only one among many that has been remade in the image of man. Our archaic view of the world in which everything is cast metal should be softening with the warming of intellectual fires. A large part of the electorate in our technically advanced nation admitted it just wasn’t ready for a woman in the role Trump is daily cocking up. It will take more hard lessons, perhaps, before even men can be made to admit that women can do it just as well, if not better. Stereotypes, after all, are eventually melted down to make way for new words. This may be one case where literalism might be a reliable guide.