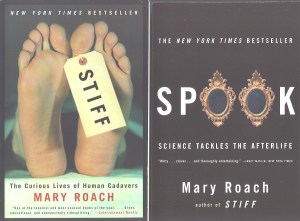

Mary Roach never fails to please. I first discovered her during a jaunt to my local, lamented Borders (not a weekend passes when I don’t mourn the chain’s closing anew) on an autumn evening when Spook leaped out at me (metaphorically) from the science section. I have read layperson-digestible science since I was in junior high school, having been a charter subscriber to Discover magazine. I was, therefore, amazed when I realized an author with some scientific credibility would take on the topic of ghosts. This was followed by Stiff, Bonk, Packing for Mars, and now, Gulp. The subtitle of Gulp, Adventures on the Alimentary Canal, captures the flavor of this book about eating. While some live to eat, we all eat to live, and it makes perfect sense that religion could come to shine a little light in this facet of human existence. Actually, although Roach doesn’t emphasize it, the ethics of eating has become a major interest in embodiment theology over the past few years. Food and faith, it turns out, are closely connected.

Mary Roach never fails to please. I first discovered her during a jaunt to my local, lamented Borders (not a weekend passes when I don’t mourn the chain’s closing anew) on an autumn evening when Spook leaped out at me (metaphorically) from the science section. I have read layperson-digestible science since I was in junior high school, having been a charter subscriber to Discover magazine. I was, therefore, amazed when I realized an author with some scientific credibility would take on the topic of ghosts. This was followed by Stiff, Bonk, Packing for Mars, and now, Gulp. The subtitle of Gulp, Adventures on the Alimentary Canal, captures the flavor of this book about eating. While some live to eat, we all eat to live, and it makes perfect sense that religion could come to shine a little light in this facet of human existence. Actually, although Roach doesn’t emphasize it, the ethics of eating has become a major interest in embodiment theology over the past few years. Food and faith, it turns out, are closely connected.

In Gulp, the one instance where religion comes into major play regards, ironically, rectal feeding. Roach points out that the question of its effectiveness had been part of discussions of fasting in the contexts of convents. Some traditions in various religions advocate denying oneself food as an act of penance or contrition. The question of whether nourishment taken without the satisfaction of eating counted, however, is one that the church took up. Characteristically not making a definitive answer, the practice mutely continues. Roach notes that clergy have been among the avowed supporters of colonic irrigation as well, making one wonder why the upper half of the alimentary canal has typically caused religions so much trouble. Of course, Roach is not writing about religion, but about eating. But still…

Religion, broken out abstractly from everything a person does, is a modern phenomenon. In fact, it is questionable whether religion can even be considered as a phenomenon of ancient societies at all since it was so thoroughly integrated into everything a person did. When priests separated themselves from laity, at least as early as ancient Sumer, the idea that one class of people could handle the requirements of the gods while the rest of us got along with the secular business of living life took hold. But religious specialists still maintained control over morals. Food, in a world of unfair distribution, will forever be an ethical issue. Instead, most religions have brought the focus down to the individual. What you eat may very well reflect your religious beliefs. Whether we feed the world or not we have, unwisely, left to politicians. As I ponder this indigestible topic, I recommend reading Gulp for a bit of relief from the serious business of the ethics of eating.