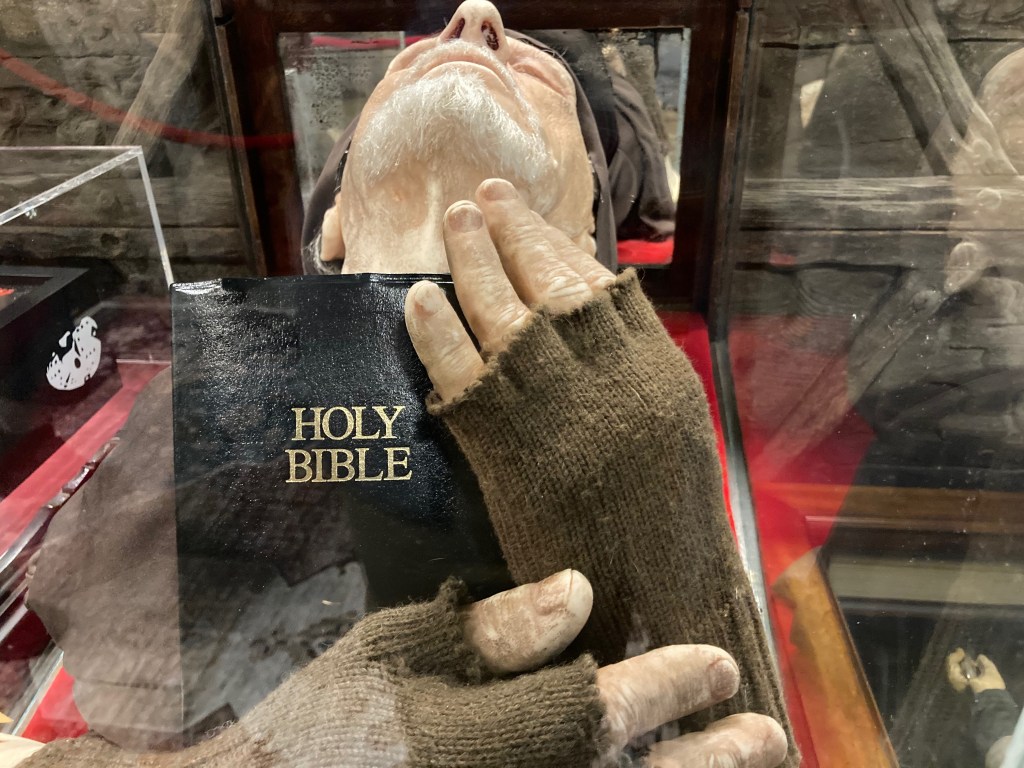

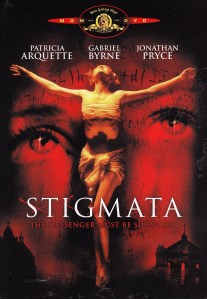

Having written Holy Horror, I keep an eye out for Bibles in horror contexts. In the context of A Nightmare in New Hope there was the torso and head of Fr. Alameida from Stigmata. In his hands he clutches a Bible. Of course, if you’ve seen Stigmata you’ll know that Alameida is already dead at this point, having been so from the start of the film. Those visiting a horror museum are likely completely nonplussed by seeing a Bible there. Much of the horror genre builds on religious themes. Witness The Nun. The original costume for her is standing over in the corner right there. If I had enough time (i.e., if I were in an academic post again) I would be spending my time trying to figure out this connection. I’ve written about religion and horror in four books, in several articles on Horror Homeroom, and in too many blog posts to remember. There is a connection that only professors have the luxury of thinking time to explore.

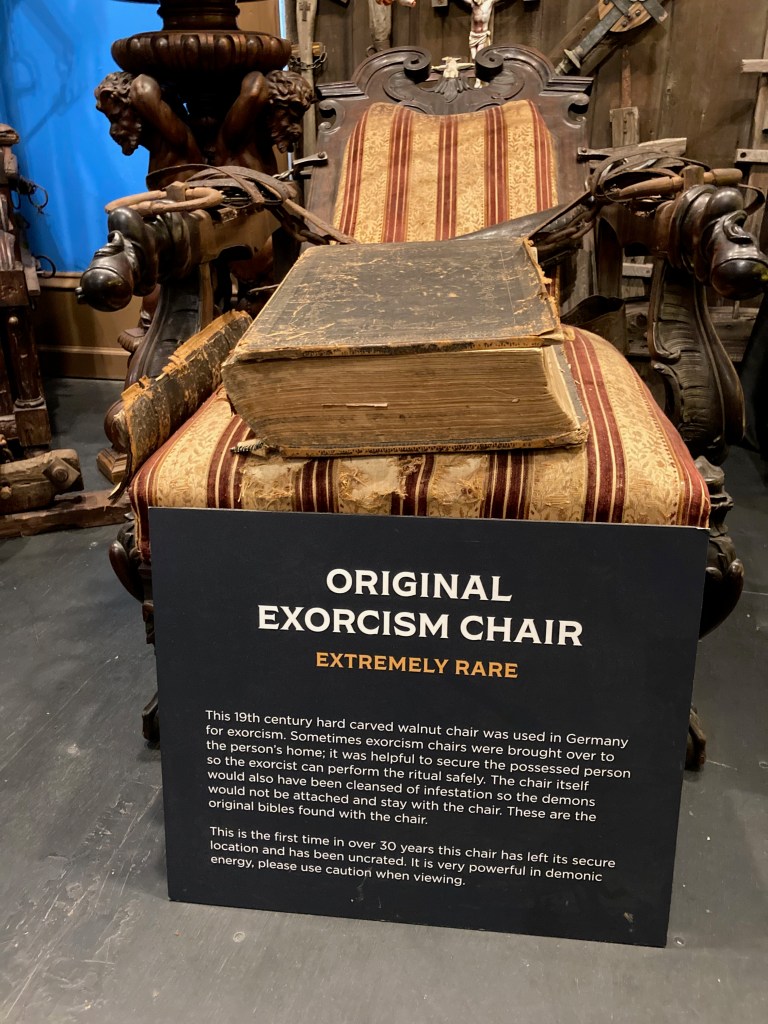

A couple hours later at Vampa, Vampire Paranormal Museum, Bibles were again in evidence. Indeed, in profusion. Vampire hunters, it seems, never wanted to be without the Good Book. Many of the vampire hunting chests (entire chests!) included a Bible. As noted in a previous post, Michael Jackson owned a vampire hunting kit for a while, until the Jehovah’s Witnesses convinced him he shouldn’t. In one of nature’s ironies, in the mail when we got back from the museum was a handwritten letter to me from the local JW Kingdom Hall. Religion and horror. Vampa also owns a rarity, an exorcism chair. Things get a bit muddy here since the chair dates from the nineteenth century but exorcism as we know it largely derives from the movie, The Exorcist. And that takes us back to New Hope.

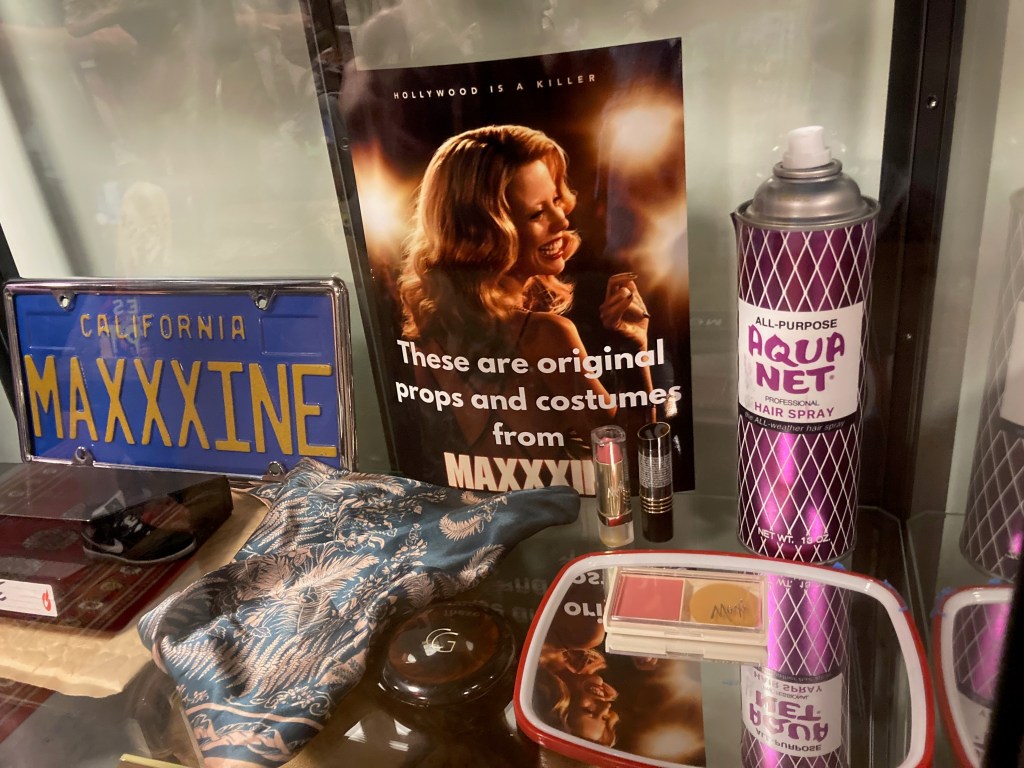

My interest was primarily in artifacts from actual movies. The Exorcist head of Regan McNeil in Nightmare in New Hope was, I believe he said, a cast. A horror museum without at least a passing reference to The Exorcist would feel strangely incomplete. And then there’s Maxxxine. The entire X trilogy is framed around religion that leads to horror, over a couple of generations. There’s a connection here and I haven’t found a convincing explanation for it yet. It’s one of the many books that I’m working on at the moment. But time is limited. And Fr. Alameida’s presence in this room, holding tight to his Bible, reminds us that the topic bears exploration.