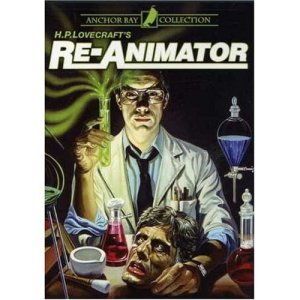

Stuart Gordon apparently had in mind to do an H. P. Lovecraft cycle, as Roger Corman did with Poe. I first saw Dagon—clearly his best—and some time later picked up Re-Animator. From Beyond was his second Lovecraft movie and it doesn’t have the visual appeal of Dagon, but it is certainly a passable gross-out for those who enjoy slimy monsters. Gordon was pretty obviously of greater libido than Lovecraft ever was. From Beyond puts sex in the spotlight’s periphery without making it absolutely central to the story. A Dr. Pretorius has built a “resonator” that allows him to see extra-dimensional beings. It does this by stimulating the pineal gland. His assistant Dr. Tillinghast, is present when a creature from, well, beyond, kills Pretorius by wrenching off his head. Tillinghast is suspected in his murder but is being held in an asylum rather than a traditional jail.

Dr. McMichaels, the love interest in the film, believes that Tillinghast is sane and that he actually did witness these beings from beyond. As a scientist, she wants to see if the resonator really works. It does, but in addition to providing the ability to experience the other realm, it also boosts the sex drive of those under its influence. She decides, against the warning of Dr. Tillinghast, to try the resonator once more, but this time the other-dimensional Pretorius has become strong enough to prevent her from shutting the machine down. Tillinghast is transformed into a modified human with an extension from his forehead and as she tries to explain what she witnessed, McMichaels is classified as insane. She and Tillinghast escape the asylum and McMichaels manages to blow up the machine, ultimately going insane for real.

Lovecraft strenuously avoided sex in his written work, limiting the number of women characters who appear. I suspect he would not have been pleased with this treatment of his story. Gordon went on to make one more Lovecraft movie beyond Dagon, a television movie of Dreams in the Witch House (which I haven’t seen). Of the three theatrical releases, I find Dagon the most convincing since the mood is serious and it seems to capture much of the feel of Lovecraft’s “Shadow over Innsmouth,” one of his best stories. Lovecraft himself apparently didn’t care that much for that particular tale. And he was critical of the conversion of stories into movies. It’s a good thing that one doesn’t have to see eye-to-eye with Lovecraft to appreciate his works. And some of them transfer to film reasonably well. Especially if you’re in the mood for slimy monsters.