The search for “free” horror has a few more reasonable offerings, it seems, if you follow the reviews. I try not to read about movies in advance, and I avoid trailers. The Woman in the Yard had higher scores than several movies streaming on the services I use. It’s Blumhouse horror, so it has a bit of substance. Substance but also some confusion. Trying to make sense of it will involve spoilers. Here goes: Ramona and David have moved into the country because Ramona found the city suffocating. Once there, however, she doesn’t take to farm living and becomes depressed. She tells her husband this and on their way home from a restaurant, he dies in an accident while she’s driving. Ramona, herself injured, tells Taylor and Annie, her son and daughter, that their father was driving. She lives with the guilt and is still struggling with depression.

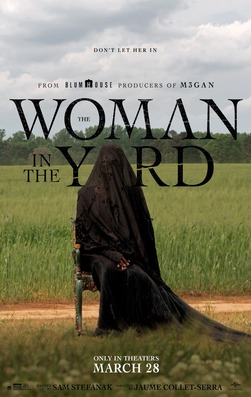

A mysterious woman shows up in the yard. Draped in black, including her face, she tells Ramona “Today’s the day.” Feeling threatened, Ramona tells the kids to stay inside, but it becomes clear that this woman is supernatural. The power is out and no phones work. The car won’t start and the nearest neighbors are a couple miles away. The family, alone, grows frightened and the woman’s shadow begins to manipulate items in the house, threatening them all. Ramona confesses to Taylor that she was responsible for his father’s death. When the woman’s shadow attacks they have to get into the dark where her shadow is powerless. Ramona is drawn through a mirror where David is still alive, but frees herself to get back to her children. The woman tells her that if she kills herself, which she’s been praying for the courage to do, her children will thrive. Without showing the death, the family is back together and the power comes on, only it is the mirror world.

A few things to note. There are a few scary moments but the movie as a whole isn’t that frightening. It is, however, dealing with suicide—it actually has, in the final credits, a note urging anyone contemplating suicide to seek help. There’s no clear indication of what happens but the ending might be interpreted rather darkly. Depression is difficult for those of us who struggle with it. The movie seems to indicate that the woman in the yard is the flip, pro-suicide version of Ramona. She appears to resist and overcome the depression, but it’s really left open at the end. Still, this isn’t bad for “free” horror. It’s thoughtful, if not exactly cheering. And it gives viewers something to think about.